View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Beardless Wildrye - Elymus triticoides

Other Names:

Leymus triticoides

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Elymus triticoides occurs throughout the western United States but in Montana has only been documented in four western counties (Barkworth in Flora of North America 2007; revised draft treatment in the Manual of Montana Vascular Plants). This grass is known from fewer than five locations which are widely scattered. Plants can be confused with Elymus smithii and/or may be overlooked in our state. Surveys that accurately identify this grass and bring forth information on locations, population sizes, habitat conditions, and threats is greatly needed.

General Description

PLANTS: A cool season perennial grass. Plants are strongly rhizomatous, not cespitose (densely tufted). Culms grow 50-100 cm tall, 1.8-3 mm thick, and are solitary or with a few together. Sources: Barkworth in Flora of North America [FNA] 2007; Lesica et al. 2012

LEAVES: Often basally concentrated. Blades are somewhat stiff, flat to inrolled, and 3-8 mm wide. Cultivated plants may have leaves to 10 mm wide. Sheaths are glabrous or hairs (1 mm or less tall). Auricles to 1 mm tall, Ligules to 1.3 mm tall, truncate, and erose. Top of leaf is usually scabrous and often sparsely. Veins are 11-27 in number, closely spaced, subequal, and prominent. Sources: Barkworth in FNA 2007; Lesica et al. 2012.

INFLORESCENCE: A spike - erect, continuous with the rachis, and 5-14 cm long. Internodes mostly glabrous and spaced 5-11.5 mm apart. Spikelets usually two per node, especially at mid-spike, 10-18 mm long. Glumes 5-16 mm long and linear, with a very narrow pointed tip (1-veined and tapers to mostly an awn (subulate) tip). Tapering begins from belong mid-length; central portion is thicker than margins. Veins are inconspicuous at mid-length. Bases of glumes do not overlap, 0.5-1.2 mm wide. Lemmas are 3-8 per spikelet, mostly hairless, and tapered to an awn tip or with a short, less than 3 mm long tip. Sources: Barkworth in FNA 2007; Lesica et al. 2012.

Phenology

Flowers late May to August (Cronquist et al. 1977).

Diagnostic Characteristics

At initial appearance

Elymus triticoides appears similar to

Agropyron smithii.

Beardless Wildrye -

Elymus triticoides, native, SOC

*Glumes: Linear to subulate. Tapering from below mid-length into a very narrow pointed tip. Their midribs not aligned with the lemma's midrib; thus, florets are twisted about 90 degrees out of alignment with the glumes, which is a feature that traditionally separates

Elymus from

Agropyron).

*Spikelets always paired at mid-spike; occasionally with 1 or 3 at bottom or top of spike.

Western Wheatgrass -

Elymus smithii, native

*Glumes: rigid and gradually tapering to a narrow sharp tip, which is often curved; their midribs usually aligned with the lemma's midrib.

*Spikelets mostly singular at mid-spike; occasionally with paired spikelets.

TAXONOMYThe treatment of perennial grasses that belong to the Triticeae Tribe is contentious among botanists.

In the

Manual of Montana Vascular Plants (Lesica et al. 2012) Lavin's treatment is more traditional, which focuses heavily on morphology:

Agropyron includes native and cultivated grasses that have spikes, usually 1 spikelet per node, several florets per spikelet, and have relatively broader glumes where the mid-ribs of glumes and lemmas align.

Elymus includes native and cultivated grasses that have spikes, having 2 or more spikelets per node where at least 2 spikelets are fertile, and/or having sharp-pointed glumes that do not align with the florets.

In the

Flora of North America (2007) Barkworth's treatment is influenced by various genetic research and the works of Love (1984) and Dewey (1984) and remains partially contentious.

Agropyron and

Elymus are split into 4 genera:

Agropyron is restricted to members with keeled glumes, are called the English Crested Wheatgrasses, and includes only the species

Agropyron cristatum.

Leymus are categorized as alkaline tolerant grasses that are strongly rhizomatous or have short, subulate glumes.

Pascopyrum is categorized as being a North American allooctoploid, which includes only the species

Pascopyrum smithii.

Pseudoroegneria species are categorized as being obligate outcrossers and have a genome that is either diploid or autotetraploid and also contains the "St" haplome. The only North American species is

Pseudoroegneria spicata.

Species Range

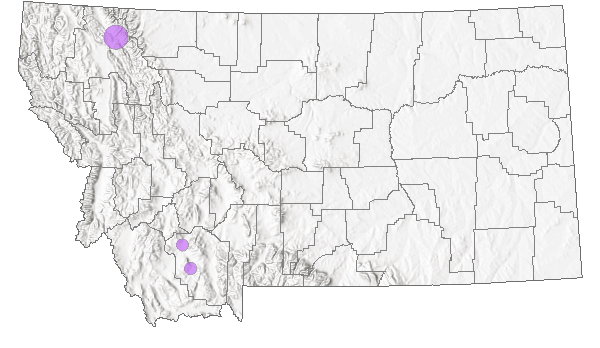

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Range Comments

Throughout most of the western (U.S.Barkworth in FNA 2007). Present in Montana along northwest border with Alberta, along south-western border with Idaho, and south-central border with Wyoming (Barkworth in FNA 2007).

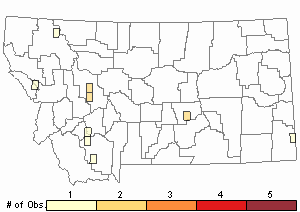

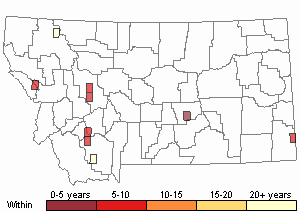

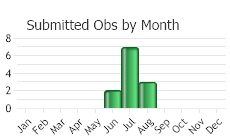

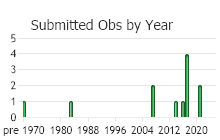

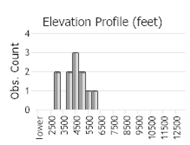

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 12

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Open, dry moderately disturbed sites at lower elevations (Lesica et al. 2012). Dry to moist, often saline meadows (Barkworth in FNA 2007).

National Vegetation Classification System Groups Associated with this Species

Wetland and Riparian

Alkaline - Saline Wetlands

Ecology

WILDLIFE INTERACTIONS

Wet meadows dominated by Beardless Wildrye provide habitat to nesting and foraging birds (Kilbride et al. 1997). In dry meadows this plant provides habitat for a variety of small mammals (McAdoo et al. 2006).

CULTURAL USES

Beardless Wildrye seeds can be ground into a flour for baking and cooking (Moerman 1998). Leaves can be used to make baskets, ropes, and other fibrous products (Moerman 1998).

Reproductive Characteristics

Plants reproduce from seed and rhizomes.

FLOWERS

Anthers are 3-6mm and dehiscent.

Economic Value

Beardless Wildrye’s strong and extensive creeping rhizomes and tolerance to lengthy flooding make it valuable in stabilizing stream bottoms and banks (USDA-NRCS 1991). Wet meadows dominated by Beardless Wildrye afford habitat to nesting and foraging birds (Kilbride et al. 1997). Various rodents make use of habitat that dry meadows with an abundance of this species offer (McAdoo et al. 2006). It provides fair forage for livestock, particularly in early spring while it is still tender (Cronquist 1977). Other uses of Beardless Wildrye include grinding seeds to prepare flour for baking and cooking, and fashioning leaves into baskets, ropes, and other fibrous products (Moerman 1998).

Management

BREVEGETATION

Beardless Wildrye’s strong and extensive creeping rhizomes and tolerance to pro-longed flooding makes it valuable in stabilizing stream bottoms and banks (USDA-NRCS 1991).

Beardless Wildrye may be grown from rhizome plugs or be seeded. Establishing stands from seed can be challenging because it has a high dormancy rate (Knapp and Wiesner 1978). In northern latitudes, seed dormancy rates can be broken by over-wintering; thus, seeding should occur in the fall. Reducing competition from weeds will improve seedling establishment. Once established, stands of Beardless Wildrye will live for many years (Young-Mathews and Winslow 2010).

NUTRITION - LIVESTOCK

Beardless Wildrye provides fair forage for livestock, particularly in early spring when it is tender (Cronquist et al. 1977).

Stewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

STATE THREAT SCORE REASON

Threat impact not assigned because threats are not known (MTNHP Threat Assessment 2021).

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Cronquist, A., A. H. Holmgren, N. H. Holmgren, J. L. Reveal, and P. K. Holmgren. 1977. Intermountain flora: Vascular Plants of the Intermountain West, U.S.A. Volume 6: The Monocotyledons. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. 584 pp.

Cronquist, A., A. H. Holmgren, N. H. Holmgren, J. L. Reveal, and P. K. Holmgren. 1977. Intermountain flora: Vascular Plants of the Intermountain West, U.S.A. Volume 6: The Monocotyledons. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. 584 pp. Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 2007. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Volume 24. Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae, Part 1. Oxford University Press, Inc., NY. xxxiii + 911 pp.

Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 2007. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Volume 24. Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae, Part 1. Oxford University Press, Inc., NY. xxxiii + 911 pp. Hitchcock, C. L., A. Cronquist, M. Ownbey, and J. W. Thompson. 1969. Vascular Plants of the Pacific Northwest. Part I: Vascular Cryptogams, Gymnosperms and Monocotyledons. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. 914 pp.

Hitchcock, C. L., A. Cronquist, M. Ownbey, and J. W. Thompson. 1969. Vascular Plants of the Pacific Northwest. Part I: Vascular Cryptogams, Gymnosperms and Monocotyledons. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. 914 pp. Kilbride, K.M., F.L. Paveglio, D.A. Pyke, M.S. Laws, and J.H. David. 1997. Use of integrated pest management to restore meadows infested with perennial pepperweed at Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. USDA Agricultural Experiment Station, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon. Special Report 972:31-35.

Kilbride, K.M., F.L. Paveglio, D.A. Pyke, M.S. Laws, and J.H. David. 1997. Use of integrated pest management to restore meadows infested with perennial pepperweed at Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. USDA Agricultural Experiment Station, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon. Special Report 972:31-35. Knapp, A.D., and L.E. Wiesner. 1978. Seed dormancy of beardless wildrye (Elymus triticoides Buckl.). Journal of Seed Technology 3(1):1-9.

Knapp, A.D., and L.E. Wiesner. 1978. Seed dormancy of beardless wildrye (Elymus triticoides Buckl.). Journal of Seed Technology 3(1):1-9. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p. McAdoo, J.K., M.R. Barrington, and M.A. Ports. 2006. Habitat affinities of rodents in northeastern Nevada rangeland communities. Western North American Naturalist 66:321-331.

McAdoo, J.K., M.R. Barrington, and M.A. Ports. 2006. Habitat affinities of rodents in northeastern Nevada rangeland communities. Western North American Naturalist 66:321-331. Moerman, D.E. 1998. Native American ethnobotany. Portland, OR: Timber Press, Inc. 927 p.

Moerman, D.E. 1998. Native American ethnobotany. Portland, OR: Timber Press, Inc. 927 p. MTNHP Threat Assessment. 2021. State Threat Score Assignment and Assessment of Reported Threats from 2006 to 2021 for State-listed Vascular Plants. Botany Program, Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana.

MTNHP Threat Assessment. 2021. State Threat Score Assignment and Assessment of Reported Threats from 2006 to 2021 for State-listed Vascular Plants. Botany Program, Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. USDA-NRCS. 1991. Conservation Plant Release Brochure for ‘Rio’ Beardless wild rye (Leymus triticoides Buckley). USDA-NRCS Ecological Sciences Division, Washington, D.C. and California Agricultural Experiment Station, UC Davis.

USDA-NRCS. 1991. Conservation Plant Release Brochure for ‘Rio’ Beardless wild rye (Leymus triticoides Buckley). USDA-NRCS Ecological Sciences Division, Washington, D.C. and California Agricultural Experiment Station, UC Davis. Young-Mathews, A. and S.R. Winslow. 2010. USDA-NRCS: Plant guide for beardless wildrye (Leymus triticoides). Lockeford, CA: USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Plant Materials Center.

Young-Mathews, A. and S.R. Winslow. 2010. USDA-NRCS: Plant guide for beardless wildrye (Leymus triticoides). Lockeford, CA: USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Plant Materials Center.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? King, L.A. 1980. Effects of topsoiling and other reclamation practices on nonseeded species establishment on surface mined land at Colstrip, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 129 p.

King, L.A. 1980. Effects of topsoiling and other reclamation practices on nonseeded species establishment on surface mined land at Colstrip, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 129 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p. Quire, R.L. 2013. The sagebrush steppe of Montana and southeastern Idaho shows evidence of high native plant diversity, stability, and resistance to the detrimental effects of nonnative plant species. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 124 p.

Quire, R.L. 2013. The sagebrush steppe of Montana and southeastern Idaho shows evidence of high native plant diversity, stability, and resistance to the detrimental effects of nonnative plant species. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 124 p.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Beardless Wildrye"