View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Railhead Milkvetch - Astragalus terminalis

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Astragalus terminalus is a regional endemic known from southwest Montana, east-central Idaho and northwest Wyoming. In Montana it is documented from Beaverhead County and the Upper Madison River Valley. The species appears to be vulnerable to intensive grazing and competition from noxious weeds, at least in low-elevation areas.

General Description

Railhead milkvetch is a tufted, taprooted perennial herb with several erect stems that reach 5-30 cm in height. The pinnately compound leaves are 5-20 cm long and have 13-21 oblong leaflets with blunt tips. Foliage is sparsely covered with forked gray hairs that branch at the base and spread in opposite directions and are appressed to the surface of leaves or stem. Dense clusters of 10-30 flowers are borne in the axils of upper leaves and become less crowded as the plant matures. The white, pea-like corollas are 12-16 mm long, with the upper petal reflexed and the lower petal purple-spotted. The calyx reaches 4-5 mm and is covered with white or black hairs. The cigar-shaped fruits are glabrous, unstalked, 3-sided in cross-section, and 15-20 mm long. The alpine ecotype is much smaller than plants from the valleys.

Phenology

Flowering takes place from June to mid-July.

Diagnostic Characteristics

Astragalus atropubescens, A. canadensis and A. scaphoides all have stalked fruits, and the latter two species usually have yellowish flowers.

Species Range

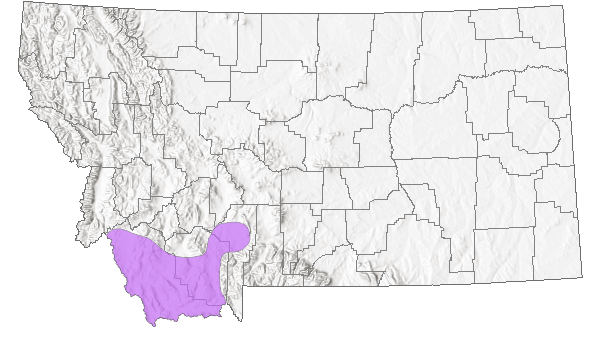

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Range Comments

Railhead milkvetch is a regional endemic of central Idaho, southwestern Montana, and northwestern Wyoming.

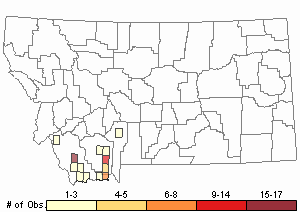

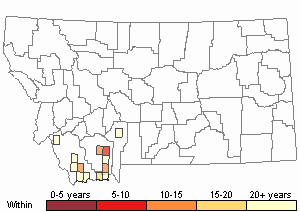

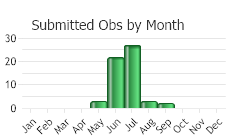

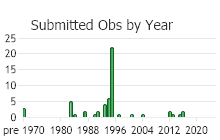

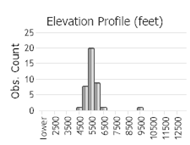

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 61

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

For the Intermountain Region, Barneby (1989) describes this species' habitat as "open, stony hillsides and benches along rivers, commonly associated with low sagebrush and calcareous bedrock." In Montana, its habitat varies widely from valley grasslands (Idaho fescue/bluebunch wheatgrass) and open eroding slopes, to ridgetops, barren clay buttes and dry subalpine meadow. Thus it is difficult to predict where this species will occur.

Southeast of Bannack, it is found on sagebrush and grassland slopes between more gentle slopes. At another site in Beaverhead County, it grows in grasslands dominated by bluebunch wheatgrass and needle-and-thread grass, sometimes with sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata and A. tripartita). In the Centennial Valley, it occurs in an Artemisia tridentata-Festuca idahoensis community. In the Upper Madison Valley, it grows in fine-textured soils at the base of eroding, sparsely vegetated slopes. This species appears to favor relatively barren sites that are often alkaline (Heidel and Vanderhorst 1996), and frequently occurs with other "barren site indicators," such as Astragalus vexilliflexus and Haplopappus acaulis (Lesica and Vanderhorst 1995).

National Vegetation Classification System Groups Associated with this Species

Shrubland

Sagebrush Shrubland

Grassland

Lowland - Prairie Grassland

Ecology

Astragalus terminalis may have the capability for prolonged dormancy, since it is morphologically similar and closely related to

A. scaphoides which has been shown to remain dormant in some years (Lesica 1995). This can result in the number of above-ground stems varying significantly among years, making accurate population counts difficult (Lesica and Steele 1994).

POLLINATORS The following animal species have been reported as pollinators of this plant species or its genus where their geographic ranges overlap:

Bombus vagans,

Bombus appositus,

Bombus auricomus,

Bombus bifarius,

Bombus borealis,

Bombus centralis,

Bombus fervidus,

Bombus flavifrons,

Bombus huntii,

Bombus mixtus,

Bombus nevadensis,

Bombus rufocinctus,

Bombus ternarius,

Bombus terricola,

Bombus occidentalis,

Bombus pensylvanicus,

Bombus griseocollis, and

Bombus insularis (Macior 1974, Thorp et al. 1983, Mayer et al. 2000, Colla and Dumesh 2010, Wilson et al. 2010, Koch et al. 2012, Miller-Struttmann and Galen 2014, Williams et al. 2014).

Management

Observations suggest that railhead milkvetch is palatable and may decrease under some livestock grazing regimes. In one exclosure in the Upper Madison Valley, plants were much denser inside than outside, and many of the plants in a nearby population had inflorescences removed, probably by game. No plants were found across the cattle guard in a grazed pasture (Heidel and Vanderhorst 1996).

Railhead milkvetch faces competition from invasive weeds, especially spotted knapweed, yellow sweet clover and cheatgrass. Centaurea maculosa (spotted knapweed) is invading this species' habitat from roadsides in the Upper Madison Valley (Heidel and Vanderhorst 1996), and has the potential to establish and compete aggressively there and in other areas. Melilotus officinalis (yellow sweet clover) and Bromus tectorum (cheatgrass) were also noted invading a site in Beaverhead County.

Stewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

STATE THREAT SCORE REASON

Reported threats to Montana’s populations of Beck Water-marigold are due to presence of non-native American Water-lily (Nymphaea odorata)

at some sites. American Water-lily has large, floating leaves, and is a strong competitor for light on the surface of standing water. Partially submerged Beck Water-marigold plants are relatively vulnerable to direct competition for light, and populations are unlikely to establish where habitat quality is damaged by non-natives.

Reported threats to Montana’s populations of Railhead Milkvetch are currently assigned as unknown (MTNHP Threat Assessment 2021). Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea stoebe) is found in the vicinity of some populations, but reports indicate that severity of impacts is unknown. Information about the severity of impacts to populations due to noxious weeds or other threats is needed.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Colla, S.R. and S. Dumesh. 2010. The bumble bees of southern Ontario: notes on natural history and distribution. Journal of the Entomological Society of Ontario 141:39-68.

Colla, S.R. and S. Dumesh. 2010. The bumble bees of southern Ontario: notes on natural history and distribution. Journal of the Entomological Society of Ontario 141:39-68. Koch, J., J. Strange, and P. Williams. 2012. Bumble bees of the western United States. Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, Pollinator Partnership. 143 p.

Koch, J., J. Strange, and P. Williams. 2012. Bumble bees of the western United States. Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, Pollinator Partnership. 143 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p. Macior, L.M. 1974. Pollination ecology of the Front Range of the Colorado Rocky Mountains. Melanderia 15: 1-59.

Macior, L.M. 1974. Pollination ecology of the Front Range of the Colorado Rocky Mountains. Melanderia 15: 1-59. Mayer, D.F., E.R. Miliczky, B.F. Finnigan, and C.A. Johnson. 2000. The bee fauna (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of southeastern Washington. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 97: 25-31.

Mayer, D.F., E.R. Miliczky, B.F. Finnigan, and C.A. Johnson. 2000. The bee fauna (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of southeastern Washington. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 97: 25-31. Miller-Struttmann, N.E. and C. Galen. 2014. High-altitude multi-taskers: bumble bee food plant use broadens along an altitudinal productivity gradient. Oecologia 176:1033-1045.

Miller-Struttmann, N.E. and C. Galen. 2014. High-altitude multi-taskers: bumble bee food plant use broadens along an altitudinal productivity gradient. Oecologia 176:1033-1045. MTNHP Threat Assessment. 2021. State Threat Score Assignment and Assessment of Reported Threats from 2006 to 2021 for State-listed Vascular Plants. Botany Program, Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana.

MTNHP Threat Assessment. 2021. State Threat Score Assignment and Assessment of Reported Threats from 2006 to 2021 for State-listed Vascular Plants. Botany Program, Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. Thorp, R.W., D.S. Horning, and L.L. Dunning. 1983. Bumble bees and cuckoo bumble bees of California (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 23:1-79.

Thorp, R.W., D.S. Horning, and L.L. Dunning. 1983. Bumble bees and cuckoo bumble bees of California (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 23:1-79. Williams, P., R. Thorp, L. Richardson, and S. Colla. 2014. Bumble Bees of North America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 208 p.

Williams, P., R. Thorp, L. Richardson, and S. Colla. 2014. Bumble Bees of North America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 208 p. Wilson, J.S., L.E. Wilson, L.D. Loftis, and T. Griswold. 2010. The montane bee fauna of north central Washington, USA, with floral associations. Western North American Naturalist 70(2): 198-207.

Wilson, J.S., L.E. Wilson, L.D. Loftis, and T. Griswold. 2010. The montane bee fauna of north central Washington, USA, with floral associations. Western North American Naturalist 70(2): 198-207.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Barneby, R.C. 1964. Atlas of North American Astragalus. 2 Vols. New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York. 1188 pp.

Barneby, R.C. 1964. Atlas of North American Astragalus. 2 Vols. New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York. 1188 pp. Barneby, R.C., A. Cronquist, A.H. Holmgren, N.H. Holmgren, J.L. Reveal, P.K. Holmgren. 1989. Fabales. Intermountain Flora: Vascular Plants of the Intermountain West, U.S.A. Volume 3, Part B. Bronx, NY: New York Botanical Garden. 279 pp.

Barneby, R.C., A. Cronquist, A.H. Holmgren, N.H. Holmgren, J.L. Reveal, P.K. Holmgren. 1989. Fabales. Intermountain Flora: Vascular Plants of the Intermountain West, U.S.A. Volume 3, Part B. Bronx, NY: New York Botanical Garden. 279 pp. Culver, D.R. 1994. Floristic analysis of the Centennial Region, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 199 pp.

Culver, D.R. 1994. Floristic analysis of the Centennial Region, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 199 pp. Heidel, B.L. and J. Vanderhorst. 1996. Sensitive plant species surveys in the Butte District, Beaverhead and Madison Counties. Unpublished report to the Bureau of Land Management. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana.

Heidel, B.L. and J. Vanderhorst. 1996. Sensitive plant species surveys in the Butte District, Beaverhead and Madison Counties. Unpublished report to the Bureau of Land Management. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. Lesica, P. 1995. Demography of Astragalus scaphoides and effects of herbivory on population growth. Great Basin Naturalist 55: 142-150.

Lesica, P. 1995. Demography of Astragalus scaphoides and effects of herbivory on population growth. Great Basin Naturalist 55: 142-150. Lesica, P. and B. M. Steele. 1994. Prolonged dormancy in vascular plants and implications for monitoring studies. Natural Areas Journal 14:209-212.

Lesica, P. and B. M. Steele. 1994. Prolonged dormancy in vascular plants and implications for monitoring studies. Natural Areas Journal 14:209-212. Lesica, P. and J. Vanderhorst. 1995. Sensitive plant survey of the Sage Creek area, Beaverhead County, Montana, Dillon Resource Area, Bureau of Land Management. Unpublished report to the Bureau of Land Management. Montana Natural Heritage Program. 36 pp. plus appendices.

Lesica, P. and J. Vanderhorst. 1995. Sensitive plant survey of the Sage Creek area, Beaverhead County, Montana, Dillon Resource Area, Bureau of Land Management. Unpublished report to the Bureau of Land Management. Montana Natural Heritage Program. 36 pp. plus appendices. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p. Vanderhorst, J.P. 1995. Sensitive plant survey in the Horse Prairie Creek drainage, Beaverhead County, Montana. Unpublished report to the Bureau of Land Management, Butte District. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. 42 pp. plus appendices.

Vanderhorst, J.P. 1995. Sensitive plant survey in the Horse Prairie Creek drainage, Beaverhead County, Montana. Unpublished report to the Bureau of Land Management, Butte District. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. 42 pp. plus appendices. Vanderhorst, J.P. and P. Lesica. 1995a. Sensitive plant survey of the Tendoy Mountains in the Beaverhead National Forest, Beaverhead County, Montana. Unpublished report to the Bureau of Land Management, Butte District. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 59 pp. plus appendices.

Vanderhorst, J.P. and P. Lesica. 1995a. Sensitive plant survey of the Tendoy Mountains in the Beaverhead National Forest, Beaverhead County, Montana. Unpublished report to the Bureau of Land Management, Butte District. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 59 pp. plus appendices.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Railhead Milkvetch"