View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Common Hound's-tongue - Cynoglossum officinale

Other Names:

Houndstongue, Gypsy-flower, Gypsyflower

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Cynoglossum officinale is a plant native to western Asia and eastern Europe and introduced into North America (Jacobs and Sing 2007). A conservation status rank is not applicable (SNA) because the plant is an exotic (non-native) in Montana that is not a suitable target for conservation activities.

General Description

PLANTS: Taprooted, biennial or short-lived perennial forbs that are densely hairy (villous) and have erect stems of 30–100 cm tall. Source: Lesica et al. 2012

LEAVES: Basal leaves are grey-green to dull green, petiolate, large, 7-25 cm long and 2-5 cm wide, and covered with dense soft hairs (villous). Blades are simple, have smooth (entire) margins, and oblanceolate to lanceolate in shape. Stem leaves are petiolate but become sessile upwards. Source: Jacobs and Sing 2007; Lesica et al. 2012

INFLORESCENCE: Flowers arranged in racemes that grow from the axils of branches and tips of stems. Pedicels are short and spreading to reflexed at maturity. Dark, reddish-purple (occasionally white) flowers are composed 5 triangular-lobed sepals that are fused to form a star-shaped calyx, and 5 petals that are fused to form a funnel-shaped corolla. Flowers are 4–5 mm long and 6–9 mm across. In fruit sepals are oblong, 5–7 mm long. The 5 stamens alternate with the fornices. The pistil has a deeply lobed ovary and a single, short, and entire style. Nutlets are ovoid, 4–7 mm long, with barbed prickles that spread at maturity. Source: Jacobs and Sing 2007; Lesica et al. 2012

The Greek words Kynos and glossa meaning ‘dog’ and ‘tongue’ combine to form Cynoglossum (Jacobs and Sing 2007). It refers to the shape and texture of the basal leaves.

Diagnostic Characteristics

Common Hound’s-tongue is characterized as a robust plant, with large hairy basal leaves, thick stems that terminate into racemes of burgundy-red flowers that each produce 4-prickly nutlets that catch your clothing like VELCRO. Occasionally flowers are white (see photo). Montana has no other Cynoglossum species.

In winter as the snow accumulates Common Hound’s-tongue plants are easy to identify from a distance. Plants remain upright and retain some of the 4-prickly nutlets.

Possible look-alikes can be found in the Family Boraginaceae where many species have prickly or sticky seeds that catch your clothing. Check out members of Lappula (Stickseed) or Hackelia (Stickseed). Species may differ in not being stout or robust plants, having flowers with different morphology, having blue flowers, having nutlets that are smaller or differently-shaped, and/or other characteristics.

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Non-native

Non-native

Range Comments

Common Hound’s-tongue is from montane zones in western Asia and eastern Europe. It was likely introduced to North America as a contaminant in grain seed. Today it occurs in almost every U.S. state and Canadian province (NRCS PLANTS database; www.plants.usda.gov).

In Montana it was first documented in 1900 in Stillwater County (Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria; www.pnwherbaria.org).

Adhikari et al. (2020) modeled the predicted future distribution of this and other weed species across the major road network in Montana under predicted future climate scenarios and found that area of predicted future habitat suitability is likely to increase.

For maps and other distributional information on non-native species see:

Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Habitat Tool (INHABIT) from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Compendium from the Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI)

EDDMapS Species Information EDDMapS Species Information

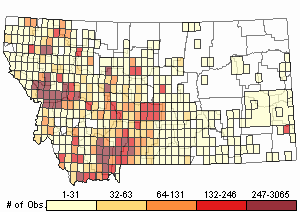

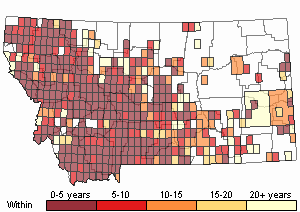

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

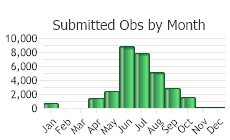

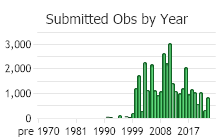

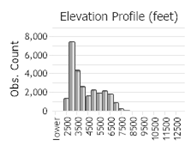

Number of Observations: 35392

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Hound’s-tongue is found in disturbed ground of pastures, fields, roadsides, grasslands, meadows, woodlands, riparian thickets in Montana (Lesica et al. 2012). It occurs in the plains and valleys of Montana (Lesica et al. 2012).

In England, plants occur on sandy soils and old dune-grasslands (Jacobs and Sing 2007). In the Netherlands it has been reported from calcareous coastal dunes (Jacobs and Sing 2007).

Ecology

CULTURALCommon Hound’s-tongue is an alternative to Comfrey because it contains

allantoin and the alkaloid

heliosupine (Tilford 1993). When applied topically it is effective on skin irritations (like insect bites) and is used internally to relieve sore throats and coughs (Tilford 1993). Like Comfrey, it should be used carefully and with moderation because Common Hound’s-tongue contains a quantity of potentially carcinogenic alkaloids (Tilford 1993).

POLLINATORS The following animal species have been reported as pollinators of this plant species or its genus where their geographic ranges overlap:

Bombus ternarius and

Bombus bimaculatus (Colla and Dumesh 2010).

Reproductive Characteristics

Plants reproduce only by seed.

FRUITS [Adapted from Jacobs and Sing 2007]

Fruits are large, thick-walled, and composed of 4-nutlets. Where the fruit comes off the plant the scar is ovate shaped. The nutlet’s thick-wall is covered by short-barbs and inside is one seed. Fruits are indehiscent, meaning they do not open at maturity. Rather the seeds remain inside the thick wall until the fruit is scarified. Moisture, cold, or other means are needed to scratch or breakdown the thick wall for the seed to germinate.

LIFE CYCLE [Adapted from Jacobs and Sing 2007]

Seeds germinate in March to April, growing into a basal rosette of large, fuzzy leaves and developing branched taproots. Branched taproots become black, thick, and can grow to depths of 3 feet in the first year. Basal leaves remain green and succulent through the entire growing season even under droughty conditions and die back after a hard frost. Come spring of the second growing season, the basal leaves re-grow from perennial buds on the root crown. In May stems sprout to a height of 30-120 cm (1-4 feet) and flower from May through July. Fruits are produced from self-pollinating or cross-pollinating flowers.

Fruits are thick-walled and covered with prickles barbed at their tips (glochidiate) which attach to people’s clothing and animal’s fur. Together the thick-wall and barbs help distribute the fruit long distances. A study in British Columbia, Canada found that 65% of mature fruits on standing plants became attached and were re-distributed by cattle in a single pasture. Fruits can remain on the plant through winter, which often makes their identification easy. Fruits that are not picked up by hitchhiker’s fall near the parent plant. Dispersal by water is ineffective or unlikely because fruits have a high specific gravity which prevents them from floating.

Management

Common Hound’s-tongue establishes, grows, and expands it populations where land is disturbed (Jacobs and Sing 2007). Plants are characterized as having a relatively low growth rate and weak ability to compete (Jacobs and Sing 2007). Thus, rapid restoration, reclamation, and/or revegetation of disturbed sites will prevent or reduce its establishment. Early detection and prevention of seed production are critical to avoiding problematic infestations (Jacobs and Sing 2007).

Management should target the flowering stages to get control on the population (Jacob and Sing 2007). An integrated vegetative management approach provides the best long-term control; it requires that land-use objectives and a desired plant community be identified (Shelly et al.

in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Once identified an integrated weed management strategy can be developed. An integrated weed management strategy promotes a weed-resistant plant community and serves other land-use objectives such as livestock forage, wildlife habitat, or recreation can be developed, making control of Common Hound’s-tongue possible.

PREVENTION [Adapted from Jacobs and Sing 2007]

Successful management seeks to control flowering to prevent seed formation and dispersal. Once established large infestations are difficult to control.

MECHANICAL and PHYSICAL CONTROL [Adapted from Jacobs and Sing 2007]

Hand-pulling can be effective, especially for small infestations. It is best to pull plants before they produce seeds. Plants should be bagged and deposited in the landfill. Pulling plants with seeds (in fruit) easily distributes them. Therefore, Plants with seeds should be bagged and burned, or bagged and allowed to desiccate or rot before disposing in the landfill. The general rule, regardless of species, is to wear gloves when weeding. It is wise to protect one’s-self against the prickly seeds and high levels of pyrrolizidine alkaloids by wearing gloves. Soil should be moist so that the entire taproot can be extracted. Roots left in the soil can re-sprout. Using a shovel might make pulling more effective because roots tend to break at the root crown.

Mowing will cut stems and reduce or prevent flowering/seeding, but will not remove plants (rosettes).

Prescribed Burning in late summer and early fall may reduce the spread of Common Hound’s-tongue because it can damage or kill plants and seeds. However, the disturbance can maintain good conditions (bare soil, low plant competition, and open canopy) for Common Hound’s-tongue to re-establish. Fire can promote seed germination form the seedbank and taproots to re-grow. A revegetation plan that encourages competitive, desirable plants should be implemented as soon as is appropriate after the prescribed burn.

Where plants have invaded cropland, a single, shallow

tilling can kill rosettes and root crowns.

Revegetating disturbed sites will prevent or greatly reduce establishment by Common Hound’s-tongue and many other exotic plants. Sustainable suppression requires revegetating with desirable plants that compete well for light, water, and nutrients. Desirable vegetation should be appropriate for the management objectives, adapted to the site conditions, and be competitive. Planting with appropriate native plants is highly encouraged. Refer to Montana Plant Materials Technical Note 46,

Seeding Rates for Conservation Species for Montana, and Extension Bulletin EB0019,

Dryland Pasture Species for Montana and Wyoming for possible species selection and seeding rates.

Revegetating land should be used, appropriately, in combination with herbicide treatment, grazing management, prescribed burning, hand-pulling and other control methods.

CHEMICAL CONTROLS [Adapted from Jacobs and Sing 2007]

Dicamba (but not picloram) and 2,4-D are auxin-type herbicides that can kill first-year rosettes. They are less effective on plants that have bolted. It is necessary to use a nonionic surfactant because the hairy leaves impedes penetration by the herbicide.

Chlorsulfuron,

metsulfuron and

trisulfuron are effective at killing Common Hound’s-tongue plants at all growth stages. Metsulfuron (0.5 ounce per acre rate) applied at the first sign of flowering will kill plants and prevent seed production. It is necessary to use a nonionic surfactant because the hairy leaves impedes penetration by the herbicide.

Imazapic (8-12 ounces per acre) should be applied with 1 quart of methylated seed oil to rosettes or bolting plants.

Although Common Hound’s-tongue is normally ignored by livestock, herbicide treatment could make plants more palatable. Therefore, grazing by domesticated animals should be suspended for 2 weeks after herbicide treatment to avoid potential poisoning.

GRAZING CONTROLS [Adapted from Jacobs and Sing 2007]

Livestock, sheep, and goats are not practical to use for controlling Common Hound’s-tongue. Plants are toxic and the risk of poisoning is possible.

Using grazing management techniques to maintain healthy, viable plant communities will resist Common Hound’s-tongue invasion.

BIOLOGICAL CONTROL [Adapted from Jacobs and Sing 2007]

Since 1988 five biological control insects have been identified for controlling Common Hound’s-tongue:

*

Root-mining Hoverfly -

Cheilosia pascuorum,

*

Hound’s-tongue Seed-feeding Weevil -

Mogulones borraginis,

*

Hound’s-tongue Stem-feeding Weevil -

Mogulones trisignatus,

*

Root-mining Flea Beetle -

Longitarsus quadriguttatus, and

*

Hound’s-tongue Root Mining Weevil -

Mogulones cruciger.

The Root-mining Flea Beetle and Hound’s-tongue Root Mining Weevil were released in British Columbia, Canada from 1997 to 1998. The Hound’s-tongue Root Mining Weevil has established better and is now distributed in Alberta. They have been significantly effective in reducing Common Hound’s-tongue.

In the U.S. release of bio-control has not been approved. This is primarily because test results also showed that insects damaged two native plants, Stickseed (

Hackelia floribunda) and Miner’s Candle (

Cryptantha elosioides). There are also concerns that bio-control insects could hurt

Cryptantha crassipes, a federally-listed endangered plant (not in Montana).

Useful Links:Central and Eastern Montana Invasive Species TeamMontana Invasive Species websiteMontana Biological Weed Control Coordination ProjectMontana Department of Agriculture - Noxious WeedsMontana Weed Control AssociationMontana Weed Control Association Contacts WebpageMontana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks - Noxious WeedsMontana State University Integrated Pest Management ExtensionWeed Publications at Montana State University Extension - MontGuidesStewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

Common Hound’s-tongue is an aggressive competitor that displaces desirable plants, reduces bio-diversity, and degrades the forage quality of grasslands, pastures, and other habitats (Jacobs and Sing 2007). It can establish monocultures. It invades and dominates forest openings that logging activities create. The large seeds are stored with energy facilitating its ability to germinate and establish quickly. Its robust taproot allows it to store energy and endure unfavorable conditions, such as drought. The fuzzy, large rosette leaves deter herbivores while effectively photosynthesizing.

The inflorescence spreads open at maturity to expose its prickly nutlets, which catch clothing, skin, or fur of neighboring travelers (Jacobs and Sing 2007). It forms a barrier for travel and makes sore fingers or tongues for those trying to remove the fruits. Sheep grazing in pastures will get fruits stuck in their wool, which causes problems for processing and decreases the market value of the wool. The nutlets can cause dermal and ocular irritation and behavior problems for cattle.

The plants are toxic to cattle, horses, and sheep; fatalities have been reported (Jacobs and Sing 2007). Common Hound’s-tongue contains high levels of pyrrolizidine alkaloids in their leaves. If ingested it can cause liver problems in deer and be fatal.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Adhikari, A., L.J. Rew, K.P. Mainali, S. Adhikari, and B.D. Maxwell. 2020. Future distribution of invasive weed species across the major road network in the state of Montana, USA. Regional Environmental Change 20(60):1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01647-0

Adhikari, A., L.J. Rew, K.P. Mainali, S. Adhikari, and B.D. Maxwell. 2020. Future distribution of invasive weed species across the major road network in the state of Montana, USA. Regional Environmental Change 20(60):1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01647-0 Colla, S.R. and S. Dumesh. 2010. The bumble bees of southern Ontario: notes on natural history and distribution. Journal of the Entomological Society of Ontario 141:39-68.

Colla, S.R. and S. Dumesh. 2010. The bumble bees of southern Ontario: notes on natural history and distribution. Journal of the Entomological Society of Ontario 141:39-68. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p. Sheley, Roger, and Janet Petroff. 1999. Biology and Management of Noxious Rangeland Weeds. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, Oregon.

Sheley, Roger, and Janet Petroff. 1999. Biology and Management of Noxious Rangeland Weeds. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, Oregon. Tilford, Gregory L. 1993. The EcoHerbalist's Fieldbook-Wildcrafting in the Mountain West. Mountain Weed Publishing, Conner, Montana.

Tilford, Gregory L. 1993. The EcoHerbalist's Fieldbook-Wildcrafting in the Mountain West. Mountain Weed Publishing, Conner, Montana.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Ament, R.J. 1995. Pioneer Plant Communities Five Years After the 1988 Yellowstone Fires. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 216 p.

Ament, R.J. 1995. Pioneer Plant Communities Five Years After the 1988 Yellowstone Fires. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 216 p. Aradottir, A.L. 1984. Ammonia volatilization from native grasslands and forests of SW Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 48 p.

Aradottir, A.L. 1984. Ammonia volatilization from native grasslands and forests of SW Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 48 p. Britton, M. P. 1955. An ecological study of a relict grassland and an adjacent grazed pasture in Beaverhead Valley, Montana. M.S. thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 23 pp.

Britton, M. P. 1955. An ecological study of a relict grassland and an adjacent grazed pasture in Beaverhead Valley, Montana. M.S. thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 23 pp. Cope, M.G. 1992. Distribution, habitat selection and survival of transplanted Columbian Sharp-tailed Grouse (Tympanuchus phasianellus columbianus) in the Tobacco Valley, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 60 p.

Cope, M.G. 1992. Distribution, habitat selection and survival of transplanted Columbian Sharp-tailed Grouse (Tympanuchus phasianellus columbianus) in the Tobacco Valley, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 60 p. Corr, D.R. 1988. Effects of stress inducing factors on musk thistle (Carduus nutans L,) including--grass competition, Rhinocyllus conicus Froel., terminal flower loss, and insecticides. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 86 p.

Corr, D.R. 1988. Effects of stress inducing factors on musk thistle (Carduus nutans L,) including--grass competition, Rhinocyllus conicus Froel., terminal flower loss, and insecticides. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 86 p. Culver, D.R. 1994. Floristic analysis of the Centennial Region, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 199 pp.

Culver, D.R. 1994. Floristic analysis of the Centennial Region, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 199 pp. Dillard, S.L. 2019. Restoring semi-arid lands with microtopography. M.Sc. Thesis. Bpzeman, MT: Montana State University. 97 p.

Dillard, S.L. 2019. Restoring semi-arid lands with microtopography. M.Sc. Thesis. Bpzeman, MT: Montana State University. 97 p. Eggers, M.J.S. 2005. Riparian vegetation of the Montana Yellowstone and cattle grazing impacts thereon. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman, MT. 125 p.

Eggers, M.J.S. 2005. Riparian vegetation of the Montana Yellowstone and cattle grazing impacts thereon. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman, MT. 125 p. Gobeille, J.E. 1992. The effect of fire on Merriams turkey brood habitat in southeastern Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 61 p.

Gobeille, J.E. 1992. The effect of fire on Merriams turkey brood habitat in southeastern Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 61 p. Grove, A.J. 1998. Effects of Douglas fir establishment in southwestern Montana mountain big sagebrush communities. M. Sc.Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 150 p.

Grove, A.J. 1998. Effects of Douglas fir establishment in southwestern Montana mountain big sagebrush communities. M. Sc.Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 150 p. Hodgson, J.R. 1970. Ecological distribution of Microtus montanus and Microtus pennsylvanicus in an area of geographic sympatry in southwestern Montana. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 65 p.

Hodgson, J.R. 1970. Ecological distribution of Microtus montanus and Microtus pennsylvanicus in an area of geographic sympatry in southwestern Montana. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 65 p. Jacobs, Jim and Sharlene Sing. 2007. Ecology and Management of Houndstongue (Cynoglossum officinale L.). July. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Bozeman, Montana

Jacobs, Jim and Sharlene Sing. 2007. Ecology and Management of Houndstongue (Cynoglossum officinale L.). July. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Bozeman, Montana Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p. Martinka, R.R. 1970. Structural characteristics and ecological relationships of male blue grouse (Dendragapus obscurus (Say)) territories in southwestern Montana. Ph.D Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 73 p.

Martinka, R.R. 1970. Structural characteristics and ecological relationships of male blue grouse (Dendragapus obscurus (Say)) territories in southwestern Montana. Ph.D Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 73 p. McColley, S.D. 2007. Restoring aspen riparian stands with beaver on the northern Yellowstone winter range. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 67 p.

McColley, S.D. 2007. Restoring aspen riparian stands with beaver on the northern Yellowstone winter range. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 67 p. Quire, R.L. 2013. The sagebrush steppe of Montana and southeastern Idaho shows evidence of high native plant diversity, stability, and resistance to the detrimental effects of nonnative plant species. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 124 p.

Quire, R.L. 2013. The sagebrush steppe of Montana and southeastern Idaho shows evidence of high native plant diversity, stability, and resistance to the detrimental effects of nonnative plant species. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 124 p. Rens, E.N. 2003. Geographical analysis of the distribution and spread of invasive plants in the Gardiner Basin, MT. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 100 p.

Rens, E.N. 2003. Geographical analysis of the distribution and spread of invasive plants in the Gardiner Basin, MT. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 100 p. Rosgaard, A.I., Jr. 1981. Ecology of the mule deer associated with the Brackett Creek winter range in the Bridger Mountains, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 76 p.

Rosgaard, A.I., Jr. 1981. Ecology of the mule deer associated with the Brackett Creek winter range in the Bridger Mountains, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 76 p. Sater, S. 2022. The insects of Sevenmile Creek, a pictorial guide to their diversity and ecology. Undergraduate Thesis. Helena, MT: Carroll College. 242 p.

Sater, S. 2022. The insects of Sevenmile Creek, a pictorial guide to their diversity and ecology. Undergraduate Thesis. Helena, MT: Carroll College. 242 p. Seipel, T.F. 2006. Plant species diversity in the sagebrush steppe of Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 87 p.

Seipel, T.F. 2006. Plant species diversity in the sagebrush steppe of Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 87 p. Simanonok, M. 2018. Plant-pollinator network assembly after wildfire. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 123 p.

Simanonok, M. 2018. Plant-pollinator network assembly after wildfire. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 123 p. Tuinstra, K. E. 1967. Vegetation of the floodplains and first terraces of Rock Creek near Red Lodge, Montana. Ph.D dissertation. Montana State University, Bozeman 110 pp.

Tuinstra, K. E. 1967. Vegetation of the floodplains and first terraces of Rock Creek near Red Lodge, Montana. Ph.D dissertation. Montana State University, Bozeman 110 pp.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Common Hound's-tongue"