View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Musk Thistle - Carduus nutans

Other Names:

Nodding Plumeless-thistle, Nodding Thistle

Non-native Species

Global Rank:

GNR

State Rank:

SNA

(see State Rank Reason below)

C-value:

0

Agency Status

USFWS:

USFS:

BLM:

External Links

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Carduus nutans is a forb native to portions of Europe, Asia, and North Africa was introduced into North America (Keil in Flora of North America 2006). A conservation status rank is not applicable (SNA) because Carduus nutans is a non-native vascular plant in Montana that is not a suitable target for conservation activities.

General Description

PLANTS: Stout, tall, biennials, occasionally annuals, with erect spiny-winged stems, 30-150 cm tall. Sources: Lesica et al. 2022

LEAVES: Basal and cauline (stem) – all spiny margined. Basal leaves have winged petioles. Stem leaves alternately arranged; reduced upwards in size. Blades oblanceolate, deeply pinnately lobed, and 10-20 cm long. Sources: Lesica et al. 2022

INFLORESCENCE: An array of racemes with solitary purple flower heads on long, wingless, and hairy (tomentose) peduncles, 2-30 cm long. Flower heads consist of involucral bracts, bristles, and disc florets (discoid) on the receptacle, 4-8 cm wide. Flower heads are erect, but nod with maturity. Involucral Bracts are lanceolate in shape, often wider than appressed base, unequal, 2-4 cm tall, and 2-7 mm wide. Forming 7-10 rows, the outer bracts spine-tipped and inner unarmed. Disc Florets have stamens and pistil (perfect), 15-25 mm long; petals purple, occasionally white, narrow, and linear-lobed. Pappus minutely barbed. Sources: Keil in Flora of North America (FNA) 2006; Giblin et al. [eds.] 2018; Lesica et al. 2022

Phenology

Across its range, seeds typically germinate in spring, and also from autumn rains (Winston et al. 2012). Flowering occurs from May through September (Keil in FNA 2006).

Diagnostic Characteristics

On first-glance thistles can look similar, but upon a closer inspection differences become apparent. Thistles belong to the genera of

Cirsium,

Carduus, and

Onopordum, which all have spiny-margined leaves and often have flower heads with spiny bracts. Ecologically, native and non-native thistles are very different.

NATIVE versus NON-NATIVE THISTLES [

Parkinson and Mangold 2015]

Native Thistles* Plants grow relatively sparsely and possess few or gentler spines, intermix with many plant species, and are slow to colonize disturbed ground.

* Flowers provide nectar and pollen for numerous native birds and insects, and forage for some wildlife. For example, elk eat the flowers of Elk Thistle.

* Involucral bracts tend to adhere to the flower head for most of their length (except for the spine).

* Plants are

not rhizomatous except for Flodman’s Thistle which can produce horizontal runner roots.

Non-native Thistles* Plants colonize disturbed ground quickly, often form dense patches, and produce nastier spines - limiting recreational activities, injuring people/animals, and reducing native plant species diversity.

* Flowers provide nectar and pollen for some birds and insects, but not forage for wildlife or livestock.

* Some species are aggressively rhizomatous and outcompete native plants that provide nutritional forage.

* Require management to control, reduce, or remove. Refer to the MANAGEMENT subsection.

DIFFERENTIATING THISTLE GENERACarduus* Stems: Winged.

* Pappus: Barbellate - minutely barbed, narrow bristles. Bristles usually fall separately.

* Flower Head - Receptacle: Not obviously fleshy or honeycombed. Densely bristly. In the flower head, look for bristles between the florets.

Cirsium* Stems: Winged or not winged.

* Pappus: Feathery (plumose) - fine, long hairs on each side of the central axis (rib).

* Flower Head - Receptacle: Densely bristly. In the flower head, look for bristles between the florets.

Onopordum* Stems: Spiny and winged along their entire length.

* Pappus: Barbellate - minutely barbed, narrow bristles. Bristles connected at base.

* Flower Head - Receptacle: Definitively fleshy and honeycombed. No or very sparse and short bristles. In the flower head, look between the florets to find nothing.

IDENTIFYING CARDUUS SPECIESThe publication by Gaskin et al. (2019) provides a dichotomous key to differentiate Turkish Thistle (

Carduus cinereus) from five other

Carduus species that occur in the Pacific Northwest.

Musk Thistle -

Carduus nutans, present, non-native and undesirable

* Plants: Usually biennial; occasionally annual.

* Flower Heads: Mostly solitary. Involucres of 2-4 cm tall and 4-8 cm wide. Nodding with maturity.

* Involucral Bracts: Appear broadly triangular – at least 2 mm wide - with smooth margins and wide at mid-length. Outer (lower) bracts spine-tipped; inner (upper) bracts unarmed.

* Disk flowers: purple.

Spiny Plumeless-thistle -

Carduus acanthoides, present, non-native and undesirable

* Plants: Annual or biennial.

* Flower Heads: Involucres spheric or hemispheric, of less than 2 cm tall and less than 4 cm wide. Several per stem and sessile or short-pedunculate. Generally, erect with maturity.

* Involucral Bracts: Appear narrowly triangular - less than 2mm wide- with smooth margins and widest at base. Outer (lower) bracts spine-tipped.

* Disk flowers: white or purple.

Turkish Thistle -

Carduus cinereus, Not documented in MT, non-native, and undesirable

* Plants: Annual.

* Flower Heads: Involucres cylindric or narrowly ellipsoid, 2 cm or less wide. Usually, pedunculate and loosely clustered at ends of branches. Peduncles are short, if present and usually winged.

* Involucral Bracts: Bracts 0.5-2.0 mm wide, usually narrower than the appressed bases. More or less persistently tomentose, and scarious-margined, especially on upper margins.

* Disk flowers: purple

TAXONOMY & NOMENCLATURECarduus nutans is part of a complex that exhibits great morphological variation (Keil

in FNA 2006). Depending upon the taxonomist, this plant has been treated as several species or as a single species with many subspecies or varieties (Keil

in FNA 2006). Plants in North America arose through multiple introductions from various taxonomic sources which cannot reliably be separated based on morphology (Winston et al. 2016). Sufficient evidence to consistently apply names to the various segregated entities is lacking (Keil

in FNA 2006).

Carduus is an old name for ‘thistle’.

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Non-native

Non-native

Range Comments

Musk Thistle is native to Europe, Asia, and northern Africa (Winston et al. 2016). Plants were introduced into North America from multiple locations beginning in the mid-1800s (Winston et al. 2016). The first records of Carduus nutans (sensu latu) in North America are from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, between 1853 and 1866 (Stuckey and Forsythe 1971), and from Chatham, New Brunswick in 1878 (Mulligan and Frankton 1954). The present North American distribution extends from the east to west coast in the deciduous forest and prairie biomes, from Canada southward through the central states. In the east, in the Great Valley of the Appalachians, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee, musk thistle is most associated with soils derived from limestone (Stuckey and Forsythe 1971, Batra 1978). In the Great Plains and the West this relationship does not necessarily hold true (Batra 1978). The near-absence of members in the Carduus nutans complex from the Great Basin and the Nebraska sandhills is probably attributable to its moisture requirements for germination. Within the Nebraska sandhills, Musk Thistle is found in pockets of finer-textured soil (Steuter personal communication).

The earliest herbarium collection of Musk Thistle in Montana was documented in 1921 in Missoula County by J. E. Kirkwood, a professor of botany at the University of Montana (MONTU 21782).

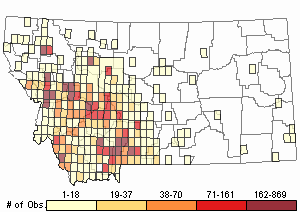

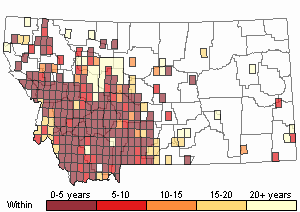

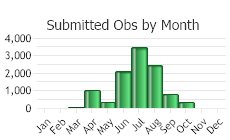

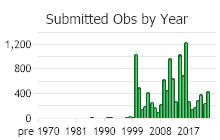

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 12044

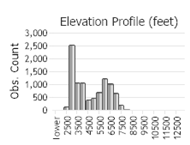

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Musk Thistle grows in fields, roadsides, disturbed grasslands, and riparian meadows in valley and montane zones in Montana (Lesica et al. 2022). Plants grow best in disturbed, neutral to acidic soils with moist conditions (Winston et al. 2016).

Ecology

POLLINATORS The following animal species have been reported as pollinators of this plant species or its genus where their geographic ranges overlap:

Bombus vagans,

Bombus auricomus,

Bombus borealis,

Bombus fervidus,

Bombus pensylvanicus,

Bombus bimaculatus,

Bombus griseocollis, and

Bombus impatiens (Thorp et al. 1983, Colla and Dumesh 2010, Williams et al. 2014, Tripoldi and Szalanski 2015).

Reproductive Characteristics

Plants reproduce by seed.

FRUIT

Fruit is a cypsela or an achene. A single flower head can produce about 1200 cypselae (Keil in FNA 2006). It is a dry, single-seeded fruit that forms from a double ovary. The pappus (calyx) of Musk Thistle separates from the achene. The pericarp (fruit wall) and seed coat are separate (free from each other). Pericarp is thick-walled, hard, nutlike, and with receptacular attachments (Keil in FNA 2006). The achene is ovoid, glabrous, and 4-5 mm long. Chromosome number of 2n=16 (Keil in FNA 2006).

HYBRIDS

Carduus nutans and Carduus acanthoides have been documented to hybridize (C. x orthocephalus) in Ontario, Canada and Wisconsin, USA where parent species co-occur (Keil in FNA 2006).

LIFE CYCLE [Adapted from Winston et al. 2012 and 2016]

Musk Thistle is typically a biennial, requiring two growing seasons to complete its life cycle. Seeds usually germinate in the spring of the first year to form a basal rosette; although autumn rains can also stimulate germination. Stems bolt in late spring to early summer. Flowering occurs from May through August or into autumn if appropriate conditions persist. Seeds remain viable for many years. Seeds are transported by water, native animals, domesticated livestock, and human activity.

Economic Value

The musk thistle complex has been found in at least 3,068 counties in 40 states in the continental USA, with 12% of those counties rating their infestation as "economic" (Dunn 1976)

Management

COUNTY & STATE DESIGNATIONSAs of 2024, Musk Thistle is listed as

County Noxious in 16 counties of Montana.

INTEGRATED VEGETATION MANAGEMENTSuccessful management of non-native thistles requires that land-use objectives and a desired plant community be identified (Shelly et al. in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Once identified, an

integrated weed management strategy that promotes a weed-resistant plant community and serves other land-use objectives, such as for livestock forage, wildlife habitat, or recreation, can be developed.

PREVENTION [Adapted from Piper in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

Preventing the establishment of non-native thistles can be accomplished by many practices:

* Learn how to differentiate “native” from “non-native” thistles and their species. Refer also to DIAGNOSTIC CHARACTERISTICS.

* Prevent vehicles from driving through, and animals from grazing within, infested areas.

* Thoroughly wash the undercarriage of vehicles and wheels in a designated area before moving to an un-infested area.

* Frequently monitor for new plants, and when found implement effective control methods (Early-Detection and Rapid-Response).

* Maintain proper grazing management that creates resilience to noxious and non-native weed invasion.

BIOLOGICAL CONTROL [Adapted from Winston et al. 2012 and 2016; Maggio and Porkorny 2019)

A variety of biocontrol agents (insects, fungi, and others) have been brought into North American to control non-native thistle plants. A fair amount of preliminary work and an array of factors must be considered when developing a biocontrol plan for controlling thistles. Readers are encouraged to consult the "Useful Links" and cited literature in this profile.

Musk Thistle was the first plant species targeted for biological control in the USA.

Biological control agents approved for Musk Thistle in the USA include:

Musk Thistle Flower Fly (

Cheilosia corydon)Nodding Thistle Gall Fly (

Urophora solstitialis) was released in Montana in 1990. Populations have not yet established on Musk Thistle.

Puccinia carduorum [fungus]

Cheilosia grossa [European hoverfly species]

Psylliodes chalcomera [flea beetle]

Biological control insects no longer approved or not recommended include:

Thistle Seedhead Weevil (

Rhinocyllus conicus) was intentionally released in 1968, in Canada, and 1969, in USA, to control exotic thistles – specifically Musk, Scotch (failed), and other species (Keil

in FNA 2006; Winston et al. 2016). After establishment, it was discovered that Thistle Seedhead Weevil fed on numerous native

Cirsium thistles. Therefore, interstate shipment permits were revoked in 2000, and Thistle Seedhead Weevil is no longer approved for re-distribution for any use. Thistle Seedhead Weevil has been documented to attack 22 of 90 native

Cirsium species in the US – even in places with non-native thistle species.

Thistle Crown Weevil (

Trichosirocalus horridus) was released in 1974, in USA, and 1975, in Canada, to control exotic thistles – specifically Musk Thistle and

Spiny Plumeless-thistle (Winston et al. 2016). However, through natural spread Thistle Crown Weevil attacked both non-native and native

Cirsium thistles. As a result, interstate transport is not permitted in the USA, and some states have prohibited re-distribution of the insect within their borders. It is critical that re-distribution of this species does not occur into places where it is either banned or not present and native thistles are known or suspected to occur.

In Montana Thistle Crown Weevil prefers Musk Thistle over Spiny Plumeless-thistle. The weevil is effective in controlling thistle populations when in combination with either other biocontrol agents and/or competition from other plant species. At many sites the insect has been ineffective with limited damage. Thistle Crown Weevil attacks the rosettes, but there has been enough survival to allow these thistles to produce some seed.

CHEMICAL CONTROLS [Adapted from Harvey and Mangold 2018]

Herbicides can be effective, especially when properly integrated with a weed management plan. The herbicide type and concentration, application time and method, environmental constraints, land use practices, local regulations, and other factors will determine its effectiveness and impact to non-target species. Strict adherence to application requirements defined on the herbicide label will reduce risks to human and environmental health. Consult your County Extension Agent and/or Weed District for information on herbicidal control. Chemical information is also available at

Greenbook.

The most widely used products include, but are not limited to:

Aminopyralid can be applied in the spring or early summer on rosettes and bolting plants or in the autumn on rosettes. Aminopyralid is less detrimental to desirable broadleaf plants – though legume species are an exception.

Clopyralid can be used on young, actively growing thistles prior to the bud stage or on rosettes in the autumn. Clopyralid does not injure established grasses.

Picloram can be used on thistles at all life stages. Picloram is a restrict-use herbicide because it is persistent, yet mobile in the soil, and can contaminate water.

Dicamba can be used on

Carduus species that are emerging or actively growing. It is best to apply on small thistles, prior to flowering, or in autumn on rosettes.

2,4-D can be used on young and actively growing annual and biennial species of non-native thistle.

Metsulfuron should be applied after emergence when non-native thistles are actively growing. Results are better when used with a nonionic or organosilicone surfactant. Restrictions on grazing or with some grass species apply with its use.

PHYSICAL CONTROLS [Adapted from Winston et al. 2012]

Tilling in agricultural settings can effectively control

Carduus species of thistle if done on a timely basis and if roots are cut below the soil surface (root crown). Tilling can be more effective when combined with an herbicide application. Tilling is not practical or desirable in wildlands or nature preserves. Tilling and disking are not compatible where biological control is used because it disrupts the organism’s life cycle.

Mowing as close to the ground, as practical, and before flower heads bloom can reduce seed production and spread of

Carduus species of thistle. Once the terminal flower heads start blooming, un-cut stems can recover, branch, flower, and seed. A single mowing treatment will not injure the root system but is effective for annual and biennial species. Mowing in the summer prior to an autumn herbicide application will improve coverage of the chemical that falls on the rosette leaves. Mowing may be incompatible with some biological control agents. Mowing should be timed appropriate to work with the life cycle of the biological control agent to prevent unwanted removal of insects, galls, etc.

CULTURAL CONTROLS [Adapted from Winston et al. 2012]

Seeding can help establish competitive native and desirable grasses and forbs where there is an infestation of

Carduus species of thistle. Typically, within two years of establishing competitive grasses biological control agents can be introduced. Establishing native and desirable competitive vegetation is one of the more successful long-term weed control methods.

Prescribed or cultural fire can control non-native thistles, but success is dependent upon the season of burn, burn severity, site conditions, and plant community composition and phenology. If used in conjunction with native plant seeding, especially those that flourish with fire, then plants will create natural competition against non-native thistles. If used in conjunction with herbicides then non-native thistle control can improve though impacts to soils should be considered. Biological control agents must be able to survive controlled burns that aid in returning native vegetation to previous thistle-infested areas – as determined by the agent, fire severity, and timing of the burn.

Grazing by livestock is generally not an effective control for non-native thistle infestations because the spiny leaves, stems, and flower heads are not very palatable. Cattle have been observed in many places to nip the flower heads of Musk Thistle and later spit them out onto the road (Pipp personal communication).

Useful Links:Central and Eastern Montana Invasive Species TeamMontana Invasive Species websiteMontana Biological Weed Control Coordination Project Field Guide for Biological Control of Weeds in Montana Montana Department of Agriculture - Noxious WeedsMontana Weed Control AssociationMontana Weed Control Association - Weed District ContactsMontana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks - Noxious WeedsMontana State University Integrated Pest Management ExtensionWeed Publications at Montana State University Extension - MontGuides

Stewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

Musk Thistle is an aggressive non-native plant that is one of the most serious weeds in North America (Keil in FNA 2006). Musk Thistle are unpalatable to wildlife and livestock. Plants can form dense, impenetrable stands in pastures and rangelands. Plants easily colonize disturbed sites that represent a wide range of vegetation types.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Colla, S.R. and S. Dumesh. 2010. The bumble bees of southern Ontario: notes on natural history and distribution. Journal of the Entomological Society of Ontario 141:39-68.

Colla, S.R. and S. Dumesh. 2010. The bumble bees of southern Ontario: notes on natural history and distribution. Journal of the Entomological Society of Ontario 141:39-68. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p. Maggio, Melissa, and Monica Pokorny. 2019. Biological Control of Invasive Plants in Montana. Invasive Species Technical Note MT-35,36. January. USDA, Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Maggio, Melissa, and Monica Pokorny. 2019. Biological Control of Invasive Plants in Montana. Invasive Species Technical Note MT-35,36. January. USDA, Natural Resources Conservation Service. Parkinson, Hilary and Jane Mangold. 2015. Guide to Exotic Thistles of Montana and How to Differentiate from Native Thistles. EB0221. Montana State University Extension, Bozeman, Montana.

Parkinson, Hilary and Jane Mangold. 2015. Guide to Exotic Thistles of Montana and How to Differentiate from Native Thistles. EB0221. Montana State University Extension, Bozeman, Montana. Thorp, R.W., D.S. Horning, and L.L. Dunning. 1983. Bumble bees and cuckoo bumble bees of California (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 23:1-79.

Thorp, R.W., D.S. Horning, and L.L. Dunning. 1983. Bumble bees and cuckoo bumble bees of California (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 23:1-79. Tripoldi, A.D. and A.L. Szalanski. 2015. The bumble bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Bombus) of Arkansas, fifty years later. Journal of Melittology 50: doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.17161/jom.v0i50.4834

Tripoldi, A.D. and A.L. Szalanski. 2015. The bumble bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Bombus) of Arkansas, fifty years later. Journal of Melittology 50: doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.17161/jom.v0i50.4834 Williams, P., R. Thorp, L. Richardson, and S. Colla. 2014. Bumble Bees of North America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 208 p.

Williams, P., R. Thorp, L. Richardson, and S. Colla. 2014. Bumble Bees of North America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 208 p. Winston, Rachel L., Carol Bell Randdall, Rosemarie De Clerck-Floate, Alec McClay, Jennifer Andreas, and Mark Schwarzlander. 2016. Field Guide For The Biological Control of Weeds In The Northwest. August 2016 Reprint. FHTET-2014-08. Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team, University of Idaho Extension and USDA Department of Agriculture.

Winston, Rachel L., Carol Bell Randdall, Rosemarie De Clerck-Floate, Alec McClay, Jennifer Andreas, and Mark Schwarzlander. 2016. Field Guide For The Biological Control of Weeds In The Northwest. August 2016 Reprint. FHTET-2014-08. Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team, University of Idaho Extension and USDA Department of Agriculture. Winston, Rachel, Rich Hansen, mark Schwarzlander, Eric Coombs, Carol Bell Randall, and Rodney Lym. 2012. Biology and Biological Control of Exotic True Thistles. Third Edition, April. FHTET-2007-05. Forest health Technology Enterprise Team, USDA, US Department of Agriculture.

Winston, Rachel, Rich Hansen, mark Schwarzlander, Eric Coombs, Carol Bell Randall, and Rodney Lym. 2012. Biology and Biological Control of Exotic True Thistles. Third Edition, April. FHTET-2007-05. Forest health Technology Enterprise Team, USDA, US Department of Agriculture.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Corr, D.R. 1988. Effects of stress inducing factors on musk thistle (Carduus nutans L,) including--grass competition, Rhinocyllus conicus Froel., terminal flower loss, and insecticides. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 86 p.

Corr, D.R. 1988. Effects of stress inducing factors on musk thistle (Carduus nutans L,) including--grass competition, Rhinocyllus conicus Froel., terminal flower loss, and insecticides. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 86 p. Lang, R.F. 1988. Interactions between ants (Hymonoptera: Formicidae) and Aphis fabae Scop. complex (Hemiptera: Aphididae), on Cirsium arvense L. Scop (Compositae). M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 29 p.

Lang, R.F. 1988. Interactions between ants (Hymonoptera: Formicidae) and Aphis fabae Scop. complex (Hemiptera: Aphididae), on Cirsium arvense L. Scop (Compositae). M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 29 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p. Mussgnug, G.L. 1972. The structure and performance of an adult population of Aulocara elliotti (Thomas) (Orthoptera, Acrididae) near Billings, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 97 p.

Mussgnug, G.L. 1972. The structure and performance of an adult population of Aulocara elliotti (Thomas) (Orthoptera, Acrididae) near Billings, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 97 p. Olliff, Tom, Roy Renkin, Craig McClure, Paul Miller, Dave Price, Dan Reinhart, and Jennifer Whipple. 2001. Managing A Complex Exotic Vegetation Program in Yellowstone National Park.

Olliff, Tom, Roy Renkin, Craig McClure, Paul Miller, Dave Price, Dan Reinhart, and Jennifer Whipple. 2001. Managing A Complex Exotic Vegetation Program in Yellowstone National Park. Quire, R.L. 2013. The sagebrush steppe of Montana and southeastern Idaho shows evidence of high native plant diversity, stability, and resistance to the detrimental effects of nonnative plant species. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 124 p.

Quire, R.L. 2013. The sagebrush steppe of Montana and southeastern Idaho shows evidence of high native plant diversity, stability, and resistance to the detrimental effects of nonnative plant species. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 124 p. Sater, S. 2022. The insects of Sevenmile Creek, a pictorial guide to their diversity and ecology. Undergraduate Thesis. Helena, MT: Carroll College. 242 p.

Sater, S. 2022. The insects of Sevenmile Creek, a pictorial guide to their diversity and ecology. Undergraduate Thesis. Helena, MT: Carroll College. 242 p. Seipel, T.F. 2006. Plant species diversity in the sagebrush steppe of Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 87 p.

Seipel, T.F. 2006. Plant species diversity in the sagebrush steppe of Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 87 p. Simanonok, M. 2018. Plant-pollinator network assembly after wildfire. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 123 p.

Simanonok, M. 2018. Plant-pollinator network assembly after wildfire. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 123 p. Simanonok, M.P. and L.A. Burkle. 2019. Nesting success of wood-cavity-nesting bees declines with increasing time since wildfire. Ecology and Evolution 9:12436-12445.

Simanonok, M.P. and L.A. Burkle. 2019. Nesting success of wood-cavity-nesting bees declines with increasing time since wildfire. Ecology and Evolution 9:12436-12445.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Musk Thistle"