View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Monarch - Danaus plexippus

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Species is rare across most of Montana and has undergone severe declines in the past decades. It faces threats from pesticide use and habitat alteration and the potential decoupling of migration cues from host plant flowering due to climate change

General Description

Monarchs are butterflies (order Lepidoptera) in the family Nymphalidae. Originally, six subspecies were named and Danaus plexippus plexippus is the only subspecies in North America. The other subspecies were described from South America (D. p. nigrippus), Puerto Rico (D. p. portoricensis), Virgin Islands (D. p. leucogyne), Tobago (D. p. tobagi), and the Caribbean and Central America (D. p. megalippe). Some disagreement still exists as to the number of subspecies and geographic distribution of Monarch subspecies, therefore Monarchs are treated at the species level under the ESA (Federal Register 2020, USFWS 2020). Western and eastern Monarchs in North America are highly related based on recent genetic evidence (Lyons et al. 2012).

Phenology

Migrating Monarchs east of the Rocky Mountains are well-documented and better understood than populations west of the Rocky Mountains (Dingle et al. 2005). In general, eastern inland Monarchs converge in Mexico each fall and overwinter, and Monarchs on the east coast migrate to Florida to overwinter (Knight and Brower 2009). On the other hand, most western populations move to southern California or congregate in Mexico to overwinter. As temperatures begin to rise in the spring, Monarchs return to their summer habitats in the northern US or southern Canada migrating =3600 km taking about 75 days to make the journey (Brower 1996). Three to five generations of butterflies make the journey annually with individuals stopping at Milkweeds to lay eggs and blooming flowers to feed along the way.

Diagnostic Characteristics

Monarchs are large butterflies with a wingspan of 8.5-12.5 mm (3.5-5.0 inches). Their wings are orange with black veins and white spots around the margin. Their large size and distinctive coloration make them one of the most well-known butterflies in the US. Males can be differentiated from females by a black dot in the hind wing vein.

Compare to the

Viceroy (Limenitis archippus), which has a notable black postmedian line crossing dorsal and ventral hindwing, perpendicular to black veins.

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Summer

Summer

Range Comments

In the New World, southern Canada and entire continental US south to South America, also many oceanic islands, overwintering in coastal California and Transvolcanic Belt of Mexico; naturalized in many other regions around the globe (Opler and Wright 1999, Glassberg 2001, and Pyle 2002); to at least 3505 m elevation in Colorado, but usually below 2745 m (Scott and Scott 1978). In Montana, reported statewide (Kohler 1980, and Stanford and Opler 1993). Common throughout the western range, except rare to uncommon in the Pacific Northwest (Glassberg 2001).

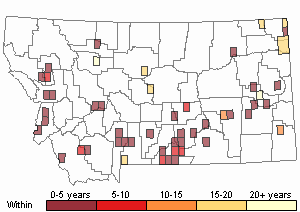

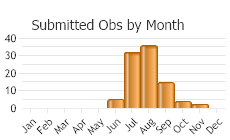

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 131

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

Species overwinters in aggregations in coastal California, Florida and Mexico. In early, spring individuals move northward over several flights to summer range. In late summer or fall a final flight moves south to overwintering sites (Scott 1986, Glassberg 2001, and Pyle 2002). Majority of southward-moving individuals west of the continental divide probably overwinter in coastal California, southward-moving individuals east of the divide probably overwinter in central Mexico, but still little data to support this.

Habitat

Open places, native prairie, foothills, open valley bottoms, open weedy fields, roadsides, pastures, marshes, suburban areas, rarely above treeline in alpine terrain during migration (Scott 1986, Opler and Wright 1999, Glassberg 2001 and Pyle 2002). Reported in Glacier National Park, Montana in mesic montane meadows (Debinski 1993).

Overwintering sites in southern Mexico are much smaller than summer habitats, but the sites must have sufficient amounts of nectar for initiating and completing migration (Alonso-mejia et al. 1997). During the Monarch’s breeding and migration season, they require trees for roosting, and Milkweeds (Asclepias sp.) to lay eggs and blooming flowers with nectar for adults to feed.

Food Habits

Larval food plants include

Apocynum, several species of

Asclepias (the primary host plant genus),

Calotropis,

Matelea, and

Sarcostemma (Scott 1986, 1992, 2006, Guppy and Shepard 2001, and Pyle 2002). Adults feed on flower nectar (including

Achillea, Apocynum, Asclepias, Aster,

Buddleia,

Chrysothamnus, Carduus, Cirsium, Cleome,

Conyza,

Cosmos,

Daucus,

Dipsacus,

Echinacea,

Echinocystis,

Eupatorium, Helianthus,

Hesperis,

Liatris, Lonicera, Machaeranthera, Medicago,

Pastinaca,

Phlox, Polygonum,

Ratibida,

Senecio, Solidago, Sonchus, Symphoricarpos, Syringa, Tagetes, Taraxacum, Trifolium, Verbena,

Vernonia,

Vicia, Zinnia) and mud (Scott 1986, 2014).

Ecology

Populations of Monarchs in the eastern United States decreased by 80-97% (Rendón-Salinas et al. 2015, The Xerces Society 2020) and western populations decreased 98% since 1997 (The Xerces Society 2020). The decline of Monarchs may be largely driven by fewer Milkweed (Ascelpias spp.), their larval host plant (e.g., Pleasants and Oberhauser 2013, Zaya et al. 2017) as well as agricultural intensification and pesticide use (e.g. Crone et al. 2019; Stenoien et al. 2018).

Reproductive Characteristics

Females lay eggs (200 or more) singly under host plant leaves, stems, and inflorescences. Eggs hatch in about 6 days (depending on temperature). Growth is rapid, to L5 and pupation in 18 days after egg-hatch. Adults emerge from pupae (eclose) in about 9-10 days. Larvae build no nests; L1-L2 instars hide in terminal shoots or under leaves, L3-L5 rest openly. Males patrol throughout the day near host plants in search of females; mating may occur at roost sites (Scott 1975b, 1986).

Management

In a

news release on December 12, 2024 the US Fish and Wildlife Service proposed listing the Monarch Butterfly under the Endangered Species Act. For more information on this species please visit the

USFWS's Monarch Status Page or

Monarch web page.

Habitat modeling for the fall migration of the western population shows that the majority of suitable nectar plant habitat is on private lands in the larger valleys of western Montana and that the Missoula and Bitterroot Valleys are of regional importance (McIntyre et al. 2024).

Stewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

In a

news release on December 15, 2020, the US Fish and Wildlife Service announced that after a review of available data on the species' status, the Monarch Butterfly warranted protection under the Endangered Species Act but listing was precluded by higher priority listing actions. The species is a candidate for listing and its status will be reviewed by the service on an annual basis. For more information on this species please visit the USFWS's Monarch Status Page (USFWS 2020) or

Monarch web page.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Alonso-Mejia, A., E. Rendon-Salinas, E. Montesinos-Patino, and L.P. Bower. 1997. Use of lipid reserves by monarch butterflies overwintering in Mexico: implications for conservation. Ecological Applications 7(3):934-947.

Alonso-Mejia, A., E. Rendon-Salinas, E. Montesinos-Patino, and L.P. Bower. 1997. Use of lipid reserves by monarch butterflies overwintering in Mexico: implications for conservation. Ecological Applications 7(3):934-947. Brower, L.P. 1996. Monarch butterfly orientation: missing pieces of a magnificent puzzle. The Journal of Experimental Biology 199:93-103.

Brower, L.P. 1996. Monarch butterfly orientation: missing pieces of a magnificent puzzle. The Journal of Experimental Biology 199:93-103. Crone, E.E., E.M. Pelton, L.M. Brown, C.C. Thomas, and C.B. Schultz. 2019. Why are monarch butterflies declining in the West? Understanding the importance of multiple correlated drivers. Ecological Applications 29(7):1-13.

Crone, E.E., E.M. Pelton, L.M. Brown, C.C. Thomas, and C.B. Schultz. 2019. Why are monarch butterflies declining in the West? Understanding the importance of multiple correlated drivers. Ecological Applications 29(7):1-13. Debinski, D. 1993. Butterflies of Glacier National Park, Montana. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Natural History, the University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas. No. 159: 1-13.

Debinski, D. 1993. Butterflies of Glacier National Park, Montana. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Natural History, the University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas. No. 159: 1-13. Dingle, H., M.P. Zalucki, W.A. Rochester, and T. Armijo-Prewitt. 2005. Distribution of the monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus (L.) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae), in western North America. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 85:491-500.

Dingle, H., M.P. Zalucki, W.A. Rochester, and T. Armijo-Prewitt. 2005. Distribution of the monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus (L.) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae), in western North America. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 85:491-500. Glassberg, J. 2001. Butterflies through Binoculars: A Field Guide to the Butterflies of Western North America. Oxford University Press.

Glassberg, J. 2001. Butterflies through Binoculars: A Field Guide to the Butterflies of Western North America. Oxford University Press. Guppy, C.S. and J.H. Shepard. 2001. Butterflies of British Columbia: including western Alberta, southern Yukon, the Alaska Panhandle, Washington, northern Oregon, northern Idaho, northwestern Montana. UBC Press (Vancouver, BC) and Royal British Columbia Museum (Victoria, BC). 414 pp.

Guppy, C.S. and J.H. Shepard. 2001. Butterflies of British Columbia: including western Alberta, southern Yukon, the Alaska Panhandle, Washington, northern Oregon, northern Idaho, northwestern Montana. UBC Press (Vancouver, BC) and Royal British Columbia Museum (Victoria, BC). 414 pp. Knight, A. and L.P. Brower. 2009. The influence of eastern North American autumnal migrant monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus L.) on continuously breeding resident monarch populations in southern Florida. Journal of Chemical Ecology 35:816-823.

Knight, A. and L.P. Brower. 2009. The influence of eastern North American autumnal migrant monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus L.) on continuously breeding resident monarch populations in southern Florida. Journal of Chemical Ecology 35:816-823. Kohler, S. 1980. Checklist of Montana Butterflies (Rhopalocera). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 34(1): 1-19.

Kohler, S. 1980. Checklist of Montana Butterflies (Rhopalocera). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 34(1): 1-19. Lyons, J.I., A.A. Pierce, S.M. Barribeau, E.D. Sternberg, A.J. Mongue, J.C. De Roode. 2012. Lack of genetic differentiation between monarch butterflies with divergent migration destinations. Molecular Ecology 21(14):3433-3444.

Lyons, J.I., A.A. Pierce, S.M. Barribeau, E.D. Sternberg, A.J. Mongue, J.C. De Roode. 2012. Lack of genetic differentiation between monarch butterflies with divergent migration destinations. Molecular Ecology 21(14):3433-3444. McIntyre, P.J., H. Ceasar, and B.E. Young. 2024. Mapping migration habitat for western monarch butterflies reveals need for public-private approach to conservation. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 12:1460363.doi: 10.3389/fevo.2024.1460363

McIntyre, P.J., H. Ceasar, and B.E. Young. 2024. Mapping migration habitat for western monarch butterflies reveals need for public-private approach to conservation. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 12:1460363.doi: 10.3389/fevo.2024.1460363 Opler, P.A. and A.B. Wright. 1999. A field guide to western butterflies. Second edition. Peterson Field Guides. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts. 540 pp.

Opler, P.A. and A.B. Wright. 1999. A field guide to western butterflies. Second edition. Peterson Field Guides. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts. 540 pp. Pleasants, J.M. and K.S. Oberhauser. 2012. Milkweed loss in agricultural fields because of herbicide use: effect on the monarch butterfly population. Insect Conservation and Diversity 6(2):135-144.

Pleasants, J.M. and K.S. Oberhauser. 2012. Milkweed loss in agricultural fields because of herbicide use: effect on the monarch butterfly population. Insect Conservation and Diversity 6(2):135-144. Pyle, R.M. 2002. The butterflies of Cascadia: a field guide to all the species of Washington, Oregon, and surrounding territories. Seattle Audubon Society, Seattle, Washington. 420 pp.

Pyle, R.M. 2002. The butterflies of Cascadia: a field guide to all the species of Washington, Oregon, and surrounding territories. Seattle Audubon Society, Seattle, Washington. 420 pp. Scott, J.A. 1975b. Mate-locating behavior of western North American butterflies. Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 14:1-40.

Scott, J.A. 1975b. Mate-locating behavior of western North American butterflies. Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 14:1-40. Scott, J.A. 1986. The butterflies of North America: a natural history and field guide. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California.

Scott, J.A. 1986. The butterflies of North America: a natural history and field guide. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California. Scott, J.A. 1992. Hostplant records for butterflies and skippers (mostly from Colorado) 1959-1992, with new life histories and notes on oviposition, immatures, and ecology. Papilio new series #6. 185 p.

Scott, J.A. 1992. Hostplant records for butterflies and skippers (mostly from Colorado) 1959-1992, with new life histories and notes on oviposition, immatures, and ecology. Papilio new series #6. 185 p. Scott, J.A. 2006. Butterfly hostplant records, 1992-2005, with a treatise on the evolution of Erynnis, and a note on new terminology for mate-locating behavior. Papilio new series #14. 74 p.

Scott, J.A. 2006. Butterfly hostplant records, 1992-2005, with a treatise on the evolution of Erynnis, and a note on new terminology for mate-locating behavior. Papilio new series #14. 74 p. Scott, J.A. 2014. Lepidoptera of North America 13. Flower visitation by Colorado butterflies (40,615 records) with a review of the literature on pollination of Colorado plants and butterfly attraction (Lepidoptera: Hersperioidea and Papilionoidea). Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthopod Diversity. Fort Collins, CO: Colorado State University. 190 p.

Scott, J.A. 2014. Lepidoptera of North America 13. Flower visitation by Colorado butterflies (40,615 records) with a review of the literature on pollination of Colorado plants and butterfly attraction (Lepidoptera: Hersperioidea and Papilionoidea). Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthopod Diversity. Fort Collins, CO: Colorado State University. 190 p. Scott, J.A. and G.R. Scott. 1978. Ecology and distribution of the butterflies of southern central Colorado. Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 17(2): 73-128.

Scott, J.A. and G.R. Scott. 1978. Ecology and distribution of the butterflies of southern central Colorado. Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 17(2): 73-128. Stanford, R.E. and P.A. Opler. 1993. Atlas of western USA butterflies: including adjacent parts of Canada and Mexico. Unpubl. Report. Denver and Fort Collins, Colorado 275 pp.

Stanford, R.E. and P.A. Opler. 1993. Atlas of western USA butterflies: including adjacent parts of Canada and Mexico. Unpubl. Report. Denver and Fort Collins, Colorado 275 pp. Stenoien, C., K.R. Nail, J.M. Zalucki, H. Parry, K.S. Oberhauser, and M.P. Zalucki. 2018. Monarchs in decline: a collateral landscape-level effect of modern agriculture. Insect Science 25(4):528-541.

Stenoien, C., K.R. Nail, J.M. Zalucki, H. Parry, K.S. Oberhauser, and M.P. Zalucki. 2018. Monarchs in decline: a collateral landscape-level effect of modern agriculture. Insect Science 25(4):528-541. The Xerces Society. 2020. Xerces Society for Insect Conservation. Accessed 21 November 2023. https://xerces.org

The Xerces Society. 2020. Xerces Society for Insect Conservation. Accessed 21 November 2023. https://xerces.org U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2020. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants: 12-month finding for the monarch butterfly. Federal Register 85(243):81813-81822.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2020. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants: 12-month finding for the monarch butterfly. Federal Register 85(243):81813-81822. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2020. Monarch (Danaus plexippus) species status assessment report, version 2.1. 120 p.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2020. Monarch (Danaus plexippus) species status assessment report, version 2.1. 120 p. Zaya, D.N., I.S. Pearse, and G. Spyreas. 2017. Long-term trends in midwestern milkweed abundances and their relevance to monarch butterfly declines. BioScience 67(4):343-356.

Zaya, D.N., I.S. Pearse, and G. Spyreas. 2017. Long-term trends in midwestern milkweed abundances and their relevance to monarch butterfly declines. BioScience 67(4):343-356.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Allen, T.J., J.P. Brock, and J. Glassberg. 2005. Caterpillars in the field and garden: a field guide to the butterfly caterpillars of North America. Oxford University Press.

Allen, T.J., J.P. Brock, and J. Glassberg. 2005. Caterpillars in the field and garden: a field guide to the butterfly caterpillars of North America. Oxford University Press. Bowers, M.D., and E.H. Williams. 1995. Variable chemical defense in the checkerspot butterfly Euphydryas gillettii (Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae). Ecological Entomology 20:208–212.

Bowers, M.D., and E.H. Williams. 1995. Variable chemical defense in the checkerspot butterfly Euphydryas gillettii (Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae). Ecological Entomology 20:208–212. Brock, J.P. and K. Kaufman. 2003. Kaufman Field Guide to Butterflies of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company, New York, NY 284 pp.

Brock, J.P. and K. Kaufman. 2003. Kaufman Field Guide to Butterflies of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company, New York, NY 284 pp. Caruthers, J.C., and D. Debinski. 2006. Montane meadow butterfly species distributions in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. University of Wyoming National Park Service Research Center Annual Report, 2006. Vol. 30, Art. 14. 85-96.

Caruthers, J.C., and D. Debinski. 2006. Montane meadow butterfly species distributions in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. University of Wyoming National Park Service Research Center Annual Report, 2006. Vol. 30, Art. 14. 85-96. Crawford, M.S. and L. Tronstad. 2020. The status and distribution of regal fritillary (Speyeria idalia) and monarch (Danaus plexippus) butterflies in eastern Wyoming. Report prepared by the WYNDD, University of Wyoming for the WY Governor's office. 23 p.

Crawford, M.S. and L. Tronstad. 2020. The status and distribution of regal fritillary (Speyeria idalia) and monarch (Danaus plexippus) butterflies in eastern Wyoming. Report prepared by the WYNDD, University of Wyoming for the WY Governor's office. 23 p. Ferris, C.D. and F.M. Brown (eds). 1981. Butterflies of the Rocky Mountains. Univ. of Oklahoma Press. Norman. 442 pp.

Ferris, C.D. and F.M. Brown (eds). 1981. Butterflies of the Rocky Mountains. Univ. of Oklahoma Press. Norman. 442 pp. Forister, M.L., C.A. Halsch, C.C. Nice, J.A. Fordyce, T.E. Dilts, J.C. Oliver, K.L. Prudic, A.M. Shapiro, J.K. Wilson, J. Glassberg. 2021. Fewer butterflies seen by community scientists across the warming and drying landscapes of the American West. Science 371:1042-1045.

Forister, M.L., C.A. Halsch, C.C. Nice, J.A. Fordyce, T.E. Dilts, J.C. Oliver, K.L. Prudic, A.M. Shapiro, J.K. Wilson, J. Glassberg. 2021. Fewer butterflies seen by community scientists across the warming and drying landscapes of the American West. Science 371:1042-1045. Forister, M.L., E.M. Grames, C.A. Halsch, K.J. Burls, C.F. Carroll, K.L. Bell, J.P. Jahner, et al. 2023. Assessing risk for butterflies in the context of climate change, demographic uncertainty, and heterogeneous data sources. Ecological Monographs 93(3):e1584. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecm.1584

Forister, M.L., E.M. Grames, C.A. Halsch, K.J. Burls, C.F. Carroll, K.L. Bell, J.P. Jahner, et al. 2023. Assessing risk for butterflies in the context of climate change, demographic uncertainty, and heterogeneous data sources. Ecological Monographs 93(3):e1584. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecm.1584 James, D.G. 2021. Western North American monarchs: spiraling into oblivion or adapting to a changing environment? Anim. Migr. 8:19-26.

James, D.G. 2021. Western North American monarchs: spiraling into oblivion or adapting to a changing environment? Anim. Migr. 8:19-26. James, D.G. and D. Nunnallee. 2011. Life histories of Cascadia butterflies. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press. 447 p.

James, D.G. and D. Nunnallee. 2011. Life histories of Cascadia butterflies. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press. 447 p. Layberry, R.A., P.W. Hall, and J.D. LaFontaine. 1998. The Butterflies of Canada. University of Toronto Press. 280 pp. + color plates.

Layberry, R.A., P.W. Hall, and J.D. LaFontaine. 1998. The Butterflies of Canada. University of Toronto Press. 280 pp. + color plates. Maxell, B.A. 2016. Northern Goshawk surveys on the Beartooth, Ashland, and Sioux Districts of the Custer-Gallatin National Forest: 2012-2014. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 114pp.

Maxell, B.A. 2016. Northern Goshawk surveys on the Beartooth, Ashland, and Sioux Districts of the Custer-Gallatin National Forest: 2012-2014. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 114pp. Scott, J.A. 1982. Mate-locating behavior of western North American butterflies. II. New observations and morphological adaptations. Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 21(3): 177-187.

Scott, J.A. 1982. Mate-locating behavior of western North American butterflies. II. New observations and morphological adaptations. Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 21(3): 177-187. Western Monarch Working Group. 2019. Western monarch butterfly conservation plan 2019-2069. Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. Version 1.0. 109 p.

Western Monarch Working Group. 2019. Western monarch butterfly conservation plan 2019-2069. Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. Version 1.0. 109 p.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Monarch"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Insects"