View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Gibson's Big Sand Tiger Beetle - Cicindela formosa gibsoni

General Description

The following comes from Wallis (1961), Acorn (2001), COSEWIC (2012), and Pearson et al. (2015). Body length is 15-17 mm; the largest tiger beetle in Montana. It is dark red to purplish above, maculations very broad and merging with each other, sometimes to the extent that elytra are mostly ivory. Metallic bluish green to violet below. Head capsule of 3rd instar larvae in Canadian populations have a non-contrasting brownish pronotum unlike the Colorado population.

Phenology

The following is taken from. Tiger beetle life cycles fit two general categories based on adult activity periods. “Spring-fall” beetles emerge as adults in late summer and fall, then overwinter in burrows before emerging again in spring when mature and ready to mate and lay eggs. The life cycle may take 1-4 years. “Summer” beetles emerge as adults in early summer, then mate and lay eggs before dying. The life cycle may take 1-2 years, possibly longer depending on latitude and elevation (Kippenhan 1994, Knisley and Schultz 1997, and Leonard and Bell 1999). Adult C. f. gibsoni in the southern part of its range are active from March to July and again August to October. At higher latitudes some adults may be present throughout summer (Kippenhan 1994, Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Pearson et al. 2015). In Montana, adults noted every month from April to mid-October (Hendricks and Roedel 2001, Hendricks and Lesica 2007, Winton 2010).

Diagnostic Characteristics

The following is largely taken from Pearson et al. (2015). This tiger beetle differs from other subspecies of

C. formosa in coloration and extent of maculations.

C. f. generosa is dull reddish brown to brown above and metallic green with coppery reflections below, with maculatons widened but distinct and joined along outer margin by a thin band.

C. f. formosa is bright coppery red above and metallic purple below with maculations connected and variably expanded such that first and rear sometimes coalesce and become obscured. Differs from the sometimes sympatric (in Canada)

Blowout Tiger Beetle (

C. lengi) by its bulkier larger size, lack of coppery underside of thorax, shorter and wider labrum, and more extensive coalesced maculations on the elytra.

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Range Comments

Localities are separated by hundreds of kilometers. This species is found in southwestern Saskatchewan and adjacent southeastern Alberta, southwestern Montana, and northwestern Colorado (Wallis 1961, Kippenhan 1994, Pearson et al. 2015), and more recently in southcentral Wyoming (French et al. 2021). Variation in phenotypic characters (coloration, extent of maculations) in C. f. gibsoni across its range is not concordant with genetic variation (French et al. 2021), and the Colorado population was recently described as a separate subspecies, C. f. gaumeri. In Montana, it is isolated from other populations of Cicindela formosa. Known only since the late 1980s in the Centennial Valley sandhills of Beaverhead County (Hendricks and Roedel 2001, Hendricks and Lesica 2007, Winton 2010, COSEWIC 2012). The Centennial Valley population varies in extent of elytra maculations from greatly expanded, similar to “C. f. fletcheri”, to completely covering the elytra except for a large midline wedge, similar to more typical C. f. gibsoni (Hendricks 2008, Winton 2010). The Centennial Valley population is most closely related genetically to Canadian populations of “C. f. fletcheri” and C. f. gibsoni (French et al. 2021), but C. f. fletcheri is considered a junior synonym of C. f. formosa (Wallis 1961), and the Centennial Valley population is neither phenotypically nor genetically alike to C. f. formosa. Perhaps C. f. fletcheri is a form of C. f. gibsoni with less extreme maculations, as genetic evidence currently suggests (COSEWIC 2012, French et al. 2021), in which case the range of gibsoni in Montana would become much more extensive, extending north to southeastern Alberta (Criddle 1925, Acorn 2001, French et al. 2021).

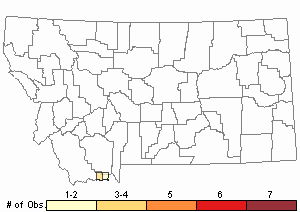

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 6

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

Non-migratory but capable of dispersal. When wings fully developed (macropterous), it is a strong agile flier and fast runner (Larochelle and Larivière 2001).

Habitat

Adult and larval tiger beetle habitat is essentially identical, the larvae live in soil burrows (Knisley and Schultz 1997). Across the range, Cicindela formosa gibsoni prefers open ground in dry upland sandy areas with sparse vegetation and no standing water (sand dunes, sand hills), often in short grass and forbs near dune margins, road cuts, sandy fields, and sand flats (Wallis 1961, Kippenhan 1994, Acorn 2001, Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Pearson et al. 2015, Bell et al. 2019, French et al. 2021). In Montana, found in partially-stabilized sandy dunes and swales, blowouts, sandy road cuts and tracks, and livestock paths in sand (Hendricks and Roedel 2001, Hendricks and Lesica 2007, Winton 2010). Sometimes occurs in patchy colonies associated with sandy habitat yet absent in other seemingly suitable sandy habitat nearby (Acorn 2001, Bell et al. 2019).

Food Habits

Larval and adult tiger beetles are predaceous. In general, both feed considerably on ants (Wallis 1961, Knisley and Schultz 1997). Larval C. f. gibsoni feed on ants, adults on ants, smaller tiger beetles, and sphecid wasps (Acorn 2001, Larochelle and Larivière 2001), and probably other small insects and spiders.

Ecology

Larval tiger beetles live in burrows and molt through three instars to pupation, which also occurs in the larval burrow. Adults make shallow burrows in soil for overnight protection, deeper burrows for overwintering. Adults are sensitive to heat and light and most active during sunny conditions. Excessive heat during midday on sunny days drives adults to seek shelter among vegetation or in burrows (Wallis 1961, Knisley and Schultz 1997).

C. f. gibsoni has a narrow range of ecological tolerance (stenotopic). Larval burrows in sand with a pit near entrance used for trapping insects, burrows closed in summer. Larval burrows may be quite dense in open sandy areas, occurring every 16-20 cm (Winton 2010). Adults are diurnal, and gregarious (frequently occurring in large numbers). They are often found sunning on warm soil, become active at 15-20°C, and burrow in sand to escape excessive heat and to overwinter (to 300 cm deep for “

C. f. fletcheri"). Predators include asilid (robber) flies. Escapes by flying quickly, typically short distances making an audible buzz while in flight, seek cover in vegetation once landing. Wary and difficult to approach. Other associated tiger beetle species include

Blowout Tiger Beetle (

C. lengi),

C. limbata,

C. lepida (=

Ellipsoptera lepida), and

C. scutellaris in Canada (Criddle 1925, Larochelle and Larivière 2001, COSEWIC 2012), and

C. decemnotata and

C. arenicola in Montana (Hendricks and Roedel 2001, Hendricks and Lesica 2007, Winton 2010, Winton et al. 2010).

Reproductive Characteristics

Life cycle of Cicindela formosa gibsoni is 2-3 years, depending on elevation and latitude (Kippenhan 1994, Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Pearson et al. 2015). In Montana, mating is reported late May to mid-July in late morning to midday with sunshine and air temperatures 21.0-24.5°C (Hendricks and Roedel 2001, Hendricks and Lesica 2007, Hendricks 2008).

Management

Considered rare and of conservation concern in Canada and the U.S. (COSEWIC 2012, Knisley et al. 2014). Sandy habitats favored by this subspecies experience vegetation encroachment and stabilization as succession proceeds, and benefit from disturbance that retains early to mid-succession conditions. Additional threats include excessive livestock grazing and agricultural encroachment (COSEWIC 2012, Knisley et al. 2014). Dune stabilization is considered the greatest threat to populations in Montana and Saskatchewan (Hendricks and Lesica 2007, Winton 2010, COSEWIC 2012, Bell et al. 2019). Some colonies (particularly the larval burrows) could be impacted by trampling through livestock overgrazing, but grazing at appropriate stocking levels and duration could also be beneficial by keeping vegetation cover more open (simulating former bison activity). Appropriate use of limited controlled burns is another tool to maintain early succession conditions so long as a spatial mosaic of suitable microhabitats is maintained and timing (mid to late autumn for controlled burns) does not overly impact late adult surface activity (Winton 2010, Knisley 2011).

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Acorn, J. 2001. Tiger beetles of Alberta: killers on the clay, stalkers on the sand. The University of Alberta Press, Edmonton, Alberta. 120 p.

Acorn, J. 2001. Tiger beetles of Alberta: killers on the clay, stalkers on the sand. The University of Alberta Press, Edmonton, Alberta. 120 p. Bell, A.J., K.S. Calladine, and I.D. Phillips. 2019. Distribution, abundance, and ecology of the threatened Gibson's Big Sand Tiger Beetle (Cicindela formosa gibsoni Brown) in the Elbow Sand Hills of Saskatchewan. Journal of Insect Conservation 23:957-965.

Bell, A.J., K.S. Calladine, and I.D. Phillips. 2019. Distribution, abundance, and ecology of the threatened Gibson's Big Sand Tiger Beetle (Cicindela formosa gibsoni Brown) in the Elbow Sand Hills of Saskatchewan. Journal of Insect Conservation 23:957-965. COSEWIC. 2012. Assessment and status report on the gibson's Big Sand Tiger Beetle Cicindela formosa gibsoni in Canada. COSEWIC, Ottowa, Ontario. ix + 42 p.

COSEWIC. 2012. Assessment and status report on the gibson's Big Sand Tiger Beetle Cicindela formosa gibsoni in Canada. COSEWIC, Ottowa, Ontario. ix + 42 p. Criddle, N. 1925. A new Cicindela from the adjacent territory of Montana and Alberta. The Canadian Entomologist 57:127-128.

Criddle, N. 1925. A new Cicindela from the adjacent territory of Montana and Alberta. The Canadian Entomologist 57:127-128. French, R.L.K., A.J. Bell, K.S. Calladine, J.H. Acorn, and F.A.H. Sperling. 2021. Genomic distinctness despite shared color patterns among threatened populations of a tiger beetle. Conservation Genetics 22:873-888.

French, R.L.K., A.J. Bell, K.S. Calladine, J.H. Acorn, and F.A.H. Sperling. 2021. Genomic distinctness despite shared color patterns among threatened populations of a tiger beetle. Conservation Genetics 22:873-888. Hendricks, P. and M. Roedel. 2001. A faunal survey of the Centennial Valley Sandhills, Beaverhead County, Montana. Report to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 44 p.

Hendricks, P. and M. Roedel. 2001. A faunal survey of the Centennial Valley Sandhills, Beaverhead County, Montana. Report to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 44 p. Hendricks, P.D. and P. Lesica. 2007. A disjunct population of Cicindela formosa (Say) in southwestern Montana, U.S.A. (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Cicindela. 39:53-58.

Hendricks, P.D. and P. Lesica. 2007. A disjunct population of Cicindela formosa (Say) in southwestern Montana, U.S.A. (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Cicindela. 39:53-58. Hendricks, Paul. 2008. Centennial Sandhills faunal survey summary: 2008. Unpublished report to The Nature Conservancy, Montana Field Office. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 4 p.

Hendricks, Paul. 2008. Centennial Sandhills faunal survey summary: 2008. Unpublished report to The Nature Conservancy, Montana Field Office. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 4 p. Kippenhan, Michael G. 1994. The Tiger Beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) of Colorado. 1994. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 120(1):1-86.

Kippenhan, Michael G. 1994. The Tiger Beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) of Colorado. 1994. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 120(1):1-86. Knisley, C.B. 2011. Anthropogenic disturbances and rare tiger beetle habitats: benefits, risks, and implications for conservation. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 4:41-61.

Knisley, C.B. 2011. Anthropogenic disturbances and rare tiger beetle habitats: benefits, risks, and implications for conservation. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 4:41-61. Knisley, C.B., and T.D. Schultz. 1997. The biology of tiger beetles and a guide to the species of the south Atlantic states. Virginia Museum of Natural History Special Publication Number 5. 210 p.

Knisley, C.B., and T.D. Schultz. 1997. The biology of tiger beetles and a guide to the species of the south Atlantic states. Virginia Museum of Natural History Special Publication Number 5. 210 p. Knisley, C.B., M. Kippenhan, and D. Brzoska. 2014. Conservation status of United States tiger beetles. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 7:93-145.

Knisley, C.B., M. Kippenhan, and D. Brzoska. 2014. Conservation status of United States tiger beetles. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 7:93-145. Larochelle, A and M Lariviere. 2001. Natural history of the tiger beetles of North America north of Mexico. Cicindela. 33:41-162.

Larochelle, A and M Lariviere. 2001. Natural history of the tiger beetles of North America north of Mexico. Cicindela. 33:41-162. Leonard, Jonathan G. and Ross T. Bell, 1999. Northeastern Tiger Beetles: a field guide to tiger beetles of New England and eastern Canada. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 176 p.

Leonard, Jonathan G. and Ross T. Bell, 1999. Northeastern Tiger Beetles: a field guide to tiger beetles of New England and eastern Canada. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 176 p. Pearson, D.L., C.B. Knisley, D.P. Duran, and C.J. Kazilek. 2015. A field guide to the tiger beetles of the United States and Canada, second edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 251 p.

Pearson, D.L., C.B. Knisley, D.P. Duran, and C.J. Kazilek. 2015. A field guide to the tiger beetles of the United States and Canada, second edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 251 p. Wallis, J.B. 1961. The Cicindelidae of Canada. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press. 74 p.

Wallis, J.B. 1961. The Cicindelidae of Canada. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press. 74 p. Winton, R. C., M. G. Kippenham, and M. A. Ivie. 2010. New state record for Cicindela arenicola Rumpp (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicindelinae) in southwestern Montana. The Coleopterists Bulletin 64(1):43-44.

Winton, R. C., M. G. Kippenham, and M. A. Ivie. 2010. New state record for Cicindela arenicola Rumpp (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicindelinae) in southwestern Montana. The Coleopterists Bulletin 64(1):43-44. Winton, R.C. 2010. The effects of succession and disturbance on Coleopteran abundance and diversity in the Centennial Sandhills. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University. Bozeman, MT. 77pp + Appendices.

Winton, R.C. 2010. The effects of succession and disturbance on Coleopteran abundance and diversity in the Centennial Sandhills. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University. Bozeman, MT. 77pp + Appendices.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Bousquet, Yves. 2012. Catalogue of Geadephaga (Coleoptera; Adephaga) of America north of Mexico. ZooKeys. 245:1-1722.

Bousquet, Yves. 2012. Catalogue of Geadephaga (Coleoptera; Adephaga) of America north of Mexico. ZooKeys. 245:1-1722.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Gibson's Big Sand Tiger Beetle"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Insects"