View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Common Loon - Gavia immer

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Species is an uncommon to rare breeding resident across parts of western Montana. It appears stable and faces low level threats.

General Description

The Common Loon is a large and mainly aquatic bird. Males are generally larger than females. Adult body length ranges from 71 to 92 cm (28 to 36 inches) with wingspans to 147 cm (58 inches). Weight varies ranging from 1.6 to 8 kg (3.5 to 17.6 lb.) with an average of about 3 to 4 kg (6.6 to 8.8 lb.) (McIntyre 1988, McIntyre and Barr 1997). The feet are located far back on the body and are large, webbed, and sweep to the side rather than forward under the belly. This trait makes it difficult for Common Loons to walk on land but allows more efficient swimming underwater.

Sexes are indistinguishable based on plumage. The head and neck of breeding adults are black with a green gloss. The back, wings and sides are also black. Scapulars and wing-coverts have large white markings, which is a distinctive field mark. The eye is red. Common Loons have a broad patch of vertical white stripes on the side of the neck and a smaller patch on the upper foreneck. The breast and belly are white and the bill is straight, heavy and black (McIntyre and Barr 1997). In the non-breeding plumage, the head, neck and upper parts are dark gray to dark brown. The cheeks, throat, and underparts are white. The bill is brownish-gray to pale bluish-gray or horn colored. The iris is brown. The tail is dark brown, tipped with white (Bent 1919, Johnsgard 1987, McIntyre 1986, 1988). Juvenile plumage is similar to the adult non-breeding plumage, although the upperparts have the most pale and more conspicuous feather margins than those of adults, and the throat and sides of the neck are more finely streaked with brown. This plumage is worn until the following summer when the birds molt into more adult-like basic plumage (Palmer 1962, McIntyre 1988).

Common Loons are known for their distinctive calls, three of which are heard on summer breeding lakes. The wail, a long almost mournful cry, the tremolo, a high pitched, rapid, five-beat call, and probably the best known is the yodel which is given only by males during territorial confrontations. Common Loons generally lay 2 subelliptical to ovoid shaped eggs which vary from deep olive to light brown in color, with irregular dark brown or black spots.

For a comprehensive review of the conservation status, habitat use, and ecology of this and other Montana bird species, please see

Marks et al. 2016, Birds of Montana.Diagnostic Characteristics

The Common Loon is a large loon with a heavy, black bill and an easily recognizable breeding plumage. The large size of the Common Loon distinguishes it from the Pacific Loon (G. pacifica) and the Red-throated Loon (G. stellata), as well as the Arctic Loon (G. arctica), which has never occurred in Montana. Only the Yellow-billed Loon (G. adamsii) is comparable in size. It, however, has a distinctive yellow bill as well as subtle differences in plumage (McIntyre and Barr 1997).

Species Range

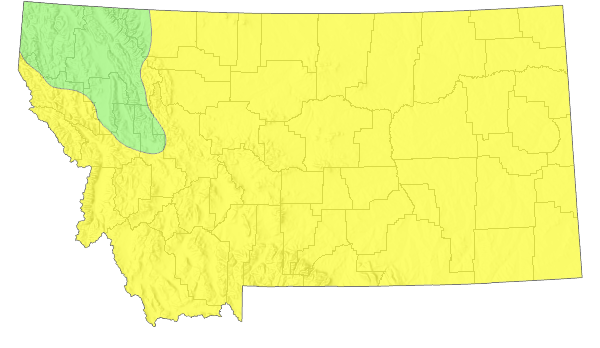

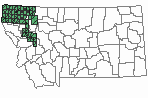

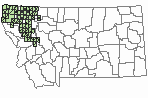

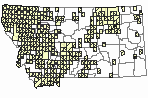

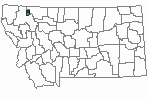

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Western Hemisphere Range

Western Hemisphere Range

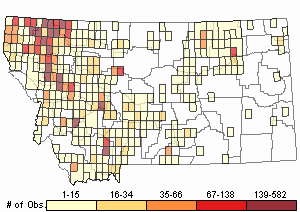

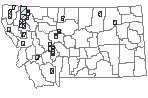

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 16734

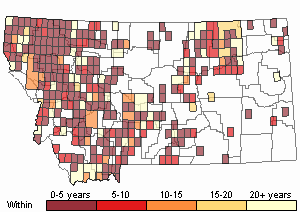

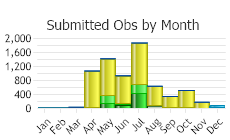

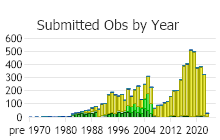

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

SUMMER (Feb 16 - Dec 14)

Direct Evidence of Breeding

Indirect Evidence of Breeding

No Evidence of Breeding

WINTER (Dec 15 - Feb 15)

Regularly Observed

Not Regularly Observed

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

In Montana, spring migration begins in early to mid-March. Fall migration starts in late August and may continue through October in Montana. Transient sightings occur throughout the state during spring migration, especially between April and June, and fall migration, between September and November (Montana Bird Distribution Committee 2012). The species is not known to remain on breeding lakes throughout the year, although there are observations of Common Loons remaining in Montana throughout the winter.

Habitat

In Montana, Common Loons will not generally nest on lakes less than about 13 acres in size or over 5000 feet in elevation (Skaar 1990). Successful nesting requires both nesting sites and nursery areas. Small islands are preferred for nesting, but herbaceous shoreline areas, especially promontories, are also selected. Nursery areas are very often sheltered, shallow coves with abundant small fish and insects (Skaar 1990). Most Montana lakes inhabited by Common Loons are relatively oligotrophic and have not experienced significant siltation or other hydrological changes.

The quantity and quality of nesting habitat limits the Common Loon population of northwest Montana. Skaar (1990) estimated the state's "carrying capacity" at 185 potential nesting territories, based on the size and number of lakes within the species' breeding distribution. He assumed 100 ha of surface area per pair. Kelly (1992) documented a density of 72.2 surface ha of water per adult Common Loon for the Tobacco, Stillwater, Clearwater, and Swan River drainages.

National Vegetation Classification System Groups Associated with this Species

Wetland and Riparian

Alkaline - Saline Wetlands

Peatland

Wet Meadow and Marsh

Food Habits

No food habit data is available for Montana. Generally, Common Loons dive from the surface and feed mainly on fishes but are opportunistic and will eat any suitable prey they can readily see and capture (McIntyre 1988) including amphibians and various invertebrates (Terres 1980). Their primary food on breeding lakes is yellow perch (Perca flavescens), followed by other shallow, warmwater fish and minnows (Cyprinidae) (Olson and Marshall 1952, Palmer 1962, Barr 1973, McIntyre 1986). Salmonids are taken on lakes that have low populations of other fish species (McIntyre 1988). On the Great Lakes, alewives (Alosa pseudoharengus) appear to be the most common prey item (McIntyre 1988). Crustaceans, especially crayfish (Decapoda), are commonly taken, and plant material is occasionally eaten (Palmer 1962, McIntyre 1988). On lakes without fish, Common Loons have been reported feeding on molluscs, insects, amphipods and amphibians (Munro 1945, Parker 1985). Young birds have a diversified diet consisting primarily of small fish and minnows, aquatic insects and crayfish (McIntyre 1988).

Winter foods are reported to include flounder (Pleuronectoidei), rock cod (Gadus morhua), herring (Clupea spp.), menhaden (Brevoortia patronus), sea trout (Salmo spp.), sculpin (Leptocottus armatus), and crabs (Palmer 1962, McIntyre 1988). A detailed study of winter-feeding patterns and preferences has not been conducted.

If nesting on a small lake, they may use an adjacent lake for supplementary foraging (Johnsgard 1987). In Ontario, Common Loons attempting to raise a chick on a fishless, acidic lake fed the chick benthic algae and possibly benthic invertebrates, but flew to other lakes to feed themselves (Alvo et al. 1988). They feed usually in waters less than 5 m deep.

Ecology

In 1985, Montana's population was estimated at at least 105 birds (Skaar 1986). No other information is available for the state. Other ecological data, from different areas in the species' range, indicate lakes smaller than 80 ha generally support only one breeding pair. Typically, territory size is larger on large lakes than on small lakes. Wintering birds may defend feeding territories during the day, and gather into rafts at night. The ecology of wintering Common Loons is not well studied. McIntyre (1978) found that loons off the Virginia coast maintained individual feeding territories of four to eight ha during the day and rafted together at night. Activity patterns were significantly correlated with tidal changes. Maintenance behavior was greatest during the mid-period of tidal rise. Feeding activities peaked late in the flood tide and during the first half of the ebb tide.

In Rhode Island, no winter-feeding territories, feeding assemblages, or tide-correlated activity patterns were noted by Daub (1989).

Reproductive Characteristics

Up to 86 lakes in Montana have had at least one pair of Common Loons present during the breeding season and up to 33 lakes have had Common Loon chicks present. On an annual basis, about 160 to 180 Common Loons can be found on Montana lakes. Between 1999 and 2001, 60% to 80% of these adults formed territorial pairs, but less than half produced chicks (Bissell 2002). Chick production in Montana has ranged between 33 and 51 chicks, with an average of 39.5 chicks produced per year. Average clutch size is 1.87 and the average chicks per successful nest (1982 to 1985) was 1.39 (Skaar 1986).

Most other reproductive data collected on Common Loons comes from studies in other areas of the species' range. These studies indicate the timing of spring arrival is correlated with latitude and dictated primarily by ice-out phenology (McIntyre 1988). Males typically return first, especially in southern breeding areas (McIntyre 1975, 1988; Sutcliffe 1980). However, pairs often arrive together at northern lakes (McIntyre 1988). Territories are established immediately after arrival and may change in size as the breeding season progresses, expanding after the chicks hatch and shrinking for failed pairs (McIntyre 1988).

Courtship begins shortly after territory reoccupation and involves quiet, shared displays including simultaneous swimming, head posturing, and short dives. Vocalizations are not extensive. Copulation sequences are stereotyped, typically last from three to ten minutes, and take place on land (McIntyre 1988). Some copulation sites become nest sites (McIntyre 1975). It is believed that pairs re-mate each spring and that courtship serves primarily to renew the pair bond (McIntyre 1988). Nest-building is conducted by both members of the pair and may immediately follow copulation, sometimes lasting over four days (McIntyre 1975, 1988). Egg laying begins one to 4.5 weeks after spring arrival and eggs are typically laid at two-day intervals (McIntyre 1975). Most clutches contain two eggs, and most one-egg clutches result from loss of the first egg (McIntyre 1975, Titus and VanDruff 1981). Both pair members incubate, beginning with the laying of the first egg, for an average period of 28 to 29 days, ranging from 26 to 31 days (Bent 1919, Olson and Marshall 1952, Palmer 1962, McIntyre 1975). An adult is present at the nest 99 percent of the time, and the eggs hatch within a day of one another (McIntyre 1975).

Chicks leave the nest within 24 hours of hatching and are soon moved to nursery areas (McIntyre 1988). Chicks are fed largely by their parents until eight weeks of age (McIntyre 1988) even though chicks are capable of short dives at the time of nest departure and may capture some fish by the second or third week (McIntyre 1975). Adults aggressively defend chicks underwater and on the surface (McIntyre 1988). Most juveniles are capable of flight at 11 to 12 weeks (Barr 1973, McIntyre 1975), and some leave their small, natal lakes or parental territories shortly afterwards (McIntyre 1975).

Common Loons appear to be faithful to breeding territories. Banded adults have been recaptured on the same breeding territory in subsequent years (McIntyre 1974, Yonge 1981). Yearly reuse of nest sites and nursery areas has been documented (Strong et al. 1987, Jung 1991), but it is not known whether the same individuals were involved. Sonograms of yodel calls suggest that individual males return to the same territory each year (McIntyre 1988, Miller 1989). Little is known about mate fidelity of breeding pairs.

Management

You can access a variety of detailed information on Common Loons and their management in Montana in the Conservation Plan for the Common Loon in Montana (Hammond 2009).

Management of Common Loons and their habitat in Montana should include multiple methods and techniques based on the management intensity level necessary on a particular lake or area. These techniques include, but are not limited to, monitoring, protection from disturbance by people, and protection of nesting and nursery habitat.

The Montana Loon Society monitors Common Loon reproduction each year in Montana. Potential breeding lakes are visited throughout the state and observations are made of adults and chicks. Observing Common Loons on lakes throughout Montana is a productive and valuable method of monitoring, but only reveals limited information; use of the lake and the production of chicks. More intensive monitoring should be implemented in areas where Common Loons are known to occur but have low nest success. This increased monitoring activity would reveal valuable information regarding nesting attempts and the timing and causes of nest failure or chick loss (Dolan 1994). Lakes where no evidence of breeding exists, but Common Loons are present, should be monitored in the spring for any sign of nesting. This added measure would assist in determining the cause of failure at these locations and would also provide a better estimate of total breeding pairs in Montana and rates of success in the population (Dolan 1994). Additional monitoring efforts should be focused on effectiveness of signs in nesting areas and nurseries. Posting floating signs is an effective management method to protect Common Loon nesting sites and nursery areas from disturbance by people. Placing informative signs in key public areas, such as boat ramps, detailing the function and reason for floating signs, and issuing press releases about Common Loons and chick sensitivity during the breeding season, are both important aspects of floating sign success or failure (Dolan 1994).

Management methods that would protect nesting and nursery habitat are varied in scope depending on the location within the state and the particular situation. Primary to the continued use of Montana lakes by Common Loons is the protection of nesting and nursery habitat from destruction resulting from construction, dredging, or filling. Avoiding artificial water level fluctuations is another technique in protecting nest site habitat. Keep water levels consistent and only allow flooding or drawdown practices to occur after the breeding cycle has been completed.

Other ways of protecting Common Loon habitat include implementing no-wake zones to prevent erosion of nesting habitat and working with homeowner associations and other owners, thereby allowing the public to become active in the protection of Common Loons and loon habitat on their lake (Dolan 1994). Common Loons are listed as a sensitive species by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 1 and they are a Species of Management Concern in Region 6 (USFWS 1995).

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Alvo, R., D. J. T. Hussell, and M. Berril. 1988. The breeding success of common loons (Gavia immer) in relation to alkalinity and other lake characteristics in Ontario. Canadian Journal of Zoology 66:746-752.

Alvo, R., D. J. T. Hussell, and M. Berril. 1988. The breeding success of common loons (Gavia immer) in relation to alkalinity and other lake characteristics in Ontario. Canadian Journal of Zoology 66:746-752. Barr, J. F. 1973. Feeding biology of the common loon (Gavia immer) in oligotrophic lakes of the Canadian shield. University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada. Ph.D. dissertation.

Barr, J. F. 1973. Feeding biology of the common loon (Gavia immer) in oligotrophic lakes of the Canadian shield. University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada. Ph.D. dissertation. Bent, A.C. 1919. Life histories of North American diving birds. U.S. National Museum Bulletin 107. Washington, D.C.

Bent, A.C. 1919. Life histories of North American diving birds. U.S. National Museum Bulletin 107. Washington, D.C. Bissell, G. 2002. Second annual common loon report. Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. 9 pp. plus appendices.

Bissell, G. 2002. Second annual common loon report. Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. 9 pp. plus appendices. Daub, B.C. 1989. Behavior of common loons in winter. Journal of Field Ornithology 60:305-311.

Daub, B.C. 1989. Behavior of common loons in winter. Journal of Field Ornithology 60:305-311. Dolan, P. M. 1994. The common loon (Gavia immer) in the northern region: biology and management recommendations. Unpublished report. U.S.D.A. Forest Service Region 1. 76 pp.

Dolan, P. M. 1994. The common loon (Gavia immer) in the northern region: biology and management recommendations. Unpublished report. U.S.D.A. Forest Service Region 1. 76 pp. Hammond, Christopher A.M. 2008. A demographic and landscape analysis for Common Loons in northwest Montana. M.S. thesis, University of Montana, Missoula.

Hammond, Christopher A.M. 2008. A demographic and landscape analysis for Common Loons in northwest Montana. M.S. thesis, University of Montana, Missoula. Johnsgard, P. A. 1987. Diving birds of North America. Univ. Nebraska Press, Lincoln. xii + 292 pp.

Johnsgard, P. A. 1987. Diving birds of North America. Univ. Nebraska Press, Lincoln. xii + 292 pp. Jung, R. E. 1991. Effects of human activities and lake characteristics on the behavior and breeding success of common loons. The Passenger Pigeon 53:207-218.

Jung, R. E. 1991. Effects of human activities and lake characteristics on the behavior and breeding success of common loons. The Passenger Pigeon 53:207-218. Kelley, L.M. 1992. The effects of human disturbance on common loon productivity in northwestern Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 65 p.

Kelley, L.M. 1992. The effects of human disturbance on common loon productivity in northwestern Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 65 p. Marks, J.S., P. Hendricks, and D. Casey. 2016. Birds of Montana. Arrington, VA. Buteo Books. 659 pages.

Marks, J.S., P. Hendricks, and D. Casey. 2016. Birds of Montana. Arrington, VA. Buteo Books. 659 pages. McIntyre, J. W. 1974. Territorial affinity of a common loon. Bird-Banding 45:178.

McIntyre, J. W. 1974. Territorial affinity of a common loon. Bird-Banding 45:178. McIntyre, J. W. 1978. Wintering behavior of common loons. Auk 95:396-403.

McIntyre, J. W. 1978. Wintering behavior of common loons. Auk 95:396-403. McIntyre, J. W. 1986. Common loon. Pages 679-95 in R. L. Di Silvestro (editor). Audubon Wildlife Report 1986. National Audubon Society, New York, New York.

McIntyre, J. W. 1986. Common loon. Pages 679-95 in R. L. Di Silvestro (editor). Audubon Wildlife Report 1986. National Audubon Society, New York, New York. McIntyre, J. W. 1988. The common loon: spirit of northern lakes. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis. x + 200 pp.

McIntyre, J. W. 1988. The common loon: spirit of northern lakes. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis. x + 200 pp. McIntyre, J.M.W. 1975. Biology and behavior of the common loon (Gavia immer) with reference to its adaptability in a man-altered environment. Ph.D. Dissertation. St. Paul, Minnesota: University of Minnesota. 243 p.

McIntyre, J.M.W. 1975. Biology and behavior of the common loon (Gavia immer) with reference to its adaptability in a man-altered environment. Ph.D. Dissertation. St. Paul, Minnesota: University of Minnesota. 243 p. Miller, E. 1989. Population turnover rate and early-season usage of multi-lake territories by common loons in upper Michigan/Wisconsin. North American Loon Fund, Meredith, New Hampshire. Unpublished report.

Miller, E. 1989. Population turnover rate and early-season usage of multi-lake territories by common loons in upper Michigan/Wisconsin. North American Loon Fund, Meredith, New Hampshire. Unpublished report. Montana Bird Distribution Committee. 2012. P.D. Skaar's Montana bird distribution. 7th Edition. Montana Audubon, Helena, Montana. 208 pp. + foldout map.

Montana Bird Distribution Committee. 2012. P.D. Skaar's Montana bird distribution. 7th Edition. Montana Audubon, Helena, Montana. 208 pp. + foldout map. Munro, J. A. 1945. Observations of the loon in the Cariboo Parklands, British Columbia. Auk 62:38-49.

Munro, J. A. 1945. Observations of the loon in the Cariboo Parklands, British Columbia. Auk 62:38-49. Olson, S. T., and W. H. Marshall. 1952. The common loon in Minnesota. Minnesota Museum of Natural History, Occasional Paper 5, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Olson, S. T., and W. H. Marshall. 1952. The common loon in Minnesota. Minnesota Museum of Natural History, Occasional Paper 5, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Palmer, R.S. 1962. Handbook of North American birds. Volume 1. Loons through flamingos. Yale University Press, New Haven. 567 pp.

Palmer, R.S. 1962. Handbook of North American birds. Volume 1. Loons through flamingos. Yale University Press, New Haven. 567 pp. Parker, K. E. 1985. Foraging and reproduction of the common loon (Gavia immer) on acidified lakes in the Adirondack Park, New York. College of Environmental Science and Forestry, State University of New York, Syracuse, New York. M.S. thesis.

Parker, K. E. 1985. Foraging and reproduction of the common loon (Gavia immer) on acidified lakes in the Adirondack Park, New York. College of Environmental Science and Forestry, State University of New York, Syracuse, New York. M.S. thesis. Skaar, D. 1990. Montana Common Loon management plan. U.S. Forest Service, Kalispell, Montana.

Skaar, D. 1990. Montana Common Loon management plan. U.S. Forest Service, Kalispell, Montana. Skaar, Don. 1986. The Montana loon study: 4th annual report. Unpublished report.

Skaar, Don. 1986. The Montana loon study: 4th annual report. Unpublished report. Strong, P. I. V., J. A. Bissonette, and J. S. Fair. 1987. Reuse of nesting and nursery areas by common loons. Journal of Wildlife Management 51:123-127.

Strong, P. I. V., J. A. Bissonette, and J. S. Fair. 1987. Reuse of nesting and nursery areas by common loons. Journal of Wildlife Management 51:123-127. Sutcliffe, S. A. 1980. Aspects of the nesting ecology of common loons in New Hampshire. University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire. M.S. thesis.

Sutcliffe, S. A. 1980. Aspects of the nesting ecology of common loons in New Hampshire. University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire. M.S. thesis. Terres, J.K. 1980. The Audubon Society encyclopedia of North American birds. Alfred A. Knopf, New York. 1109 pp.

Terres, J.K. 1980. The Audubon Society encyclopedia of North American birds. Alfred A. Knopf, New York. 1109 pp. Titus, J. R., and L. W. VanDruff. 1981. Response of the common loon to recreational pressure in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, northeastern Minnesota. Wildlife Monographs 79:1-59.

Titus, J. R., and L. W. VanDruff. 1981. Response of the common loon to recreational pressure in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, northeastern Minnesota. Wildlife Monographs 79:1-59. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Migratory Bird Management. 1995. Migratory nongame birds of management concern in the United States: the 1995 list. U.S. Government Printing Office: 1996-404-911/44014. 22 pp.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Migratory Bird Management. 1995. Migratory nongame birds of management concern in the United States: the 1995 list. U.S. Government Printing Office: 1996-404-911/44014. 22 pp. Yonge, K. S. 1981. The breeding cycle and annual production of the common loon (Gavia immer) in the boreal forest region. Thesis. University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba. 131 p.

Yonge, K. S. 1981. The breeding cycle and annual production of the common loon (Gavia immer) in the boreal forest region. Thesis. University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba. 131 p.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? [WWPC] Washington Water Power Company. 1995. 1994 wildlife report Noxon Rapids and Cabinet Gorge Reservoirs. Washington Water Power Company. Spokane, WA.

[WWPC] Washington Water Power Company. 1995. 1994 wildlife report Noxon Rapids and Cabinet Gorge Reservoirs. Washington Water Power Company. Spokane, WA. Alexander, L. L. 1985. Trouble with loons. Living Bird Quarterly. 4:10-13.

Alexander, L. L. 1985. Trouble with loons. Living Bird Quarterly. 4:10-13. Alvo, R. 1981. Marsh nesting of common loons (Gavia immer). Canadian Field Naturalist 95:357.

Alvo, R. 1981. Marsh nesting of common loons (Gavia immer). Canadian Field Naturalist 95:357. American Ornithologists Union. 1983. Checklist of North American birds, 6th Edition. 877 PP.

American Ornithologists Union. 1983. Checklist of North American birds, 6th Edition. 877 PP. American Ornithologists’ Union [AOU]. 1998. Check-list of North American birds, 7th edition. American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C. 829 p.

American Ornithologists’ Union [AOU]. 1998. Check-list of North American birds, 7th edition. American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C. 829 p. Atkinson, E.C. 1991. Distribution and status of Harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) and common loons (Gavia immer) on the Targhee National Forest. Cooperative Challenge Cost Share Project Report. Targhee National Forest and Idaho Dept. of Fish and Game. 43 p.

Atkinson, E.C. 1991. Distribution and status of Harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) and common loons (Gavia immer) on the Targhee National Forest. Cooperative Challenge Cost Share Project Report. Targhee National Forest and Idaho Dept. of Fish and Game. 43 p. Atkinson, E.G. 1991. Distribution of harlequin ducks ( Histrionicus histrionicus ) and common loons (Gavia immer) on the Targee National Forest. Coop. Challenge Cost Share Proj. Targee Natl. For. and Id. Dept. Fish Game.

Atkinson, E.G. 1991. Distribution of harlequin ducks ( Histrionicus histrionicus ) and common loons (Gavia immer) on the Targee National Forest. Coop. Challenge Cost Share Proj. Targee Natl. For. and Id. Dept. Fish Game. Barklow, W. E., and J. A. Chamberlain. 1984. The use of the tremolo call during mobbing by the common loon. Journal of Field Ornithology 55:258-9.

Barklow, W. E., and J. A. Chamberlain. 1984. The use of the tremolo call during mobbing by the common loon. Journal of Field Ornithology 55:258-9. Barr, J.F. 1986. Population dynamics of the Common Loon (Gavia immer) associated with mercury contaminated waters in northwestern Ontario. Canadian Wildife Service Occ. Paper, no. 56. 25 pp.

Barr, J.F. 1986. Population dynamics of the Common Loon (Gavia immer) associated with mercury contaminated waters in northwestern Ontario. Canadian Wildife Service Occ. Paper, no. 56. 25 pp. Bull, J. 1974. Birds of New York state. Doubleday/Natural History Press, Garden City, New York. Reprint, 1985 (with Supplement, Federation of New York Bird Clubs, 1976), Cornell Univ. Press, Ithaca, New York.

Bull, J. 1974. Birds of New York state. Doubleday/Natural History Press, Garden City, New York. Reprint, 1985 (with Supplement, Federation of New York Bird Clubs, 1976), Cornell Univ. Press, Ithaca, New York. Casey, D. 2000. Partners in Flight Draft Bird Conservation Plan Montana. Version 1.0. 287 pp.

Casey, D. 2000. Partners in Flight Draft Bird Conservation Plan Montana. Version 1.0. 287 pp. Casey, D. 2005. Rocky Mountain Front avian inventory. Final report. Prepared for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and The Nature Conservancy by the American Bird Conservancy, Kalispell, Montana.

Casey, D. 2005. Rocky Mountain Front avian inventory. Final report. Prepared for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and The Nature Conservancy by the American Bird Conservancy, Kalispell, Montana. Clark, T.W., H.A. Harvey, R.D. Dorn, D.L. Genter, and C. Groves (eds). 1989. Rare, sensitive, and threatened species of the greater Yellowstone ecosystem. Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative, Montana Natural Heritage Program, The Nature Conservancy, and Mountain West Environmental Services. 153 p.

Clark, T.W., H.A. Harvey, R.D. Dorn, D.L. Genter, and C. Groves (eds). 1989. Rare, sensitive, and threatened species of the greater Yellowstone ecosystem. Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative, Montana Natural Heritage Program, The Nature Conservancy, and Mountain West Environmental Services. 153 p. Confluence Consulting Inc. 2010. Montana Department of Transportation Wetland Mitigation Monitoring Reports (various sites). MDT Helena, MT.

Confluence Consulting Inc. 2010. Montana Department of Transportation Wetland Mitigation Monitoring Reports (various sites). MDT Helena, MT. Corkran, C. C. 1988. Status and potential for breeding of the common loon in the Pacific Northwest. Pp. 107-116 in: Papers from the 1987 conference on loon research and management. Paul Strong, (ed). North American Loon Fund, Meredith, NH. 214 pp.

Corkran, C. C. 1988. Status and potential for breeding of the common loon in the Pacific Northwest. Pp. 107-116 in: Papers from the 1987 conference on loon research and management. Paul Strong, (ed). North American Loon Fund, Meredith, NH. 214 pp. Desgranges, J.L., and P. Laporte. 1979. Preliminary consideration of the status of loons (Gaviidae) in Quebec. Report to Joint Committee of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario, Canada.

Desgranges, J.L., and P. Laporte. 1979. Preliminary consideration of the status of loons (Gaviidae) in Quebec. Report to Joint Committee of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario, Canada. Dulin, G. S. 1987. Pre-fledging feeding behavior and sibling rivalry in common loons. Central Michigan University, Mt. Pleasant, Michigan. M.S. thesis.

Dulin, G. S. 1987. Pre-fledging feeding behavior and sibling rivalry in common loons. Central Michigan University, Mt. Pleasant, Michigan. M.S. thesis. ECON, Inc. (Ecological Consulting Service), Helena, MT., 1977, Colstrip 10 x 20 Area wildlife and wildlife habitat annual monitoring report, 1977. Proj. 164-85-A. December 31, 1977.

ECON, Inc. (Ecological Consulting Service), Helena, MT., 1977, Colstrip 10 x 20 Area wildlife and wildlife habitat annual monitoring report, 1977. Proj. 164-85-A. December 31, 1977. Ehrlich, P., D. Dobkin, and D. Wheye. 1988. The birder’s handbook: a field guide to the natural history of North American birds. Simon and Schuster Inc. New York. 785 pp.

Ehrlich, P., D. Dobkin, and D. Wheye. 1988. The birder’s handbook: a field guide to the natural history of North American birds. Simon and Schuster Inc. New York. 785 pp. Fair, J. S. 1990. Water level fluctuations and common loon nest failure. Pages 57-63 in S. Sutcliffe (editor). Proceedings of the second North American conference on common loon research and management. National Udubon Sociey, New York New York.

Fair, J. S. 1990. Water level fluctuations and common loon nest failure. Pages 57-63 in S. Sutcliffe (editor). Proceedings of the second North American conference on common loon research and management. National Udubon Sociey, New York New York. Fay, L. D. 1966. Type E botulism in Great Lakes water birds. Pages 139-149 in Trans. Thiry-first N. Amer. Wild. and Nat. Res. Conf.

Fay, L. D. 1966. Type E botulism in Great Lakes water birds. Pages 139-149 in Trans. Thiry-first N. Amer. Wild. and Nat. Res. Conf. Feigley, H. P. 1997. Colonial nesting bird survey on the Bureau of Land Management Lewistown District: 1996. Unpublished report, U.S. Bureau of Land Management, Lewistown, Montana.

Feigley, H. P. 1997. Colonial nesting bird survey on the Bureau of Land Management Lewistown District: 1996. Unpublished report, U.S. Bureau of Land Management, Lewistown, Montana. Flath, Dennis and David Dickson. 1994 Systematic wildlife observations on the Blackfoot-Clearwater Wildlife Management Area 1991-1993. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks.

Flath, Dennis and David Dickson. 1994 Systematic wildlife observations on the Blackfoot-Clearwater Wildlife Management Area 1991-1993. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks. Fox, G.A., K.S. Yonge, and S.G. Sealy. 1980. Breeding performance, pollutant burden and eggshell thinning in common loons Gavia immer nesting on a boreal forest lake. Ornis Scand. 11:243-8.

Fox, G.A., K.S. Yonge, and S.G. Sealy. 1980. Breeding performance, pollutant burden and eggshell thinning in common loons Gavia immer nesting on a boreal forest lake. Ornis Scand. 11:243-8. Frank, R., H. Lumsden, J.F. Barr, and H.E. Braun. 1983. Residues of organochlorine insecticides, industrial chemicals, and mercury in eggs and tissues taken from healthy and emaciated common loons, Ontario, Canada, 1968-1980. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 12:641-654.

Frank, R., H. Lumsden, J.F. Barr, and H.E. Braun. 1983. Residues of organochlorine insecticides, industrial chemicals, and mercury in eggs and tissues taken from healthy and emaciated common loons, Ontario, Canada, 1968-1980. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 12:641-654. Gelatt, T.S. and J.D. Kelley. 1995. Western painted turtles, Chrysemys picta bellii, basking on a nesting common loon, Gavia immer. Canadian Field Naturalist 109(4): 456-45

Gelatt, T.S. and J.D. Kelley. 1995. Western painted turtles, Chrysemys picta bellii, basking on a nesting common loon, Gavia immer. Canadian Field Naturalist 109(4): 456-45 Haney, J. C. 1990. Winter habitat of common loons on the continental shelf of the southeastern United States. Wilson Bull. 102:253-263.

Haney, J. C. 1990. Winter habitat of common loons on the continental shelf of the southeastern United States. Wilson Bull. 102:253-263. Hays, R., R.L. Eng, and C.V. Davis (preparers). 1984. A list of Montana birds. Helena, MT: MT Dept. of Fish, Wildlife & Parks.

Hays, R., R.L. Eng, and C.V. Davis (preparers). 1984. A list of Montana birds. Helena, MT: MT Dept. of Fish, Wildlife & Parks. Heglund, P.S., J.R. Jones, L.H. Fredrickson, and M.S. Kaiser. 1994. Use of boreal forested wetlands by Pacific Loons (Gavia immer, Lawrence) and Horned Grebes (Podiceps auritus, L.): relations with limnological characteristics. Hydrobiologia 279/280: 171-183.

Heglund, P.S., J.R. Jones, L.H. Fredrickson, and M.S. Kaiser. 1994. Use of boreal forested wetlands by Pacific Loons (Gavia immer, Lawrence) and Horned Grebes (Podiceps auritus, L.): relations with limnological characteristics. Hydrobiologia 279/280: 171-183. Heimburger, M.D., D. Euler, and J. Barr. 1983. The impact of cottage development on common loon reproductive success in central Ontario. Wilson Bulletin 95:431-439.

Heimburger, M.D., D. Euler, and J. Barr. 1983. The impact of cottage development on common loon reproductive success in central Ontario. Wilson Bulletin 95:431-439. Johnsgard, P.A. 1979. Birds of the Great Plains: breeding species and their distribution. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. 539 pp.

Johnsgard, P.A. 1979. Birds of the Great Plains: breeding species and their distribution. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. 539 pp. Johnsgard, P.A. 1992. Birds of the Rocky Mountains with particular reference to national parks in the northern Rocky Mountain region. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. xi + 504 pp.

Johnsgard, P.A. 1992. Birds of the Rocky Mountains with particular reference to national parks in the northern Rocky Mountain region. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. xi + 504 pp. Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society.

Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society. Kaveney, D. E., and C. C. Rimmer. 1989. The breeding status of common loons in Vermont--1989. Vermont Inst. Nat. Sci., Woodstock, Vermont. Unpublished report.

Kaveney, D. E., and C. C. Rimmer. 1989. The breeding status of common loons in Vermont--1989. Vermont Inst. Nat. Sci., Woodstock, Vermont. Unpublished report. Kerekes, J., R. Tordon, A. Nieuwburg, and L. Risk. 1994. Fish eating bird abundance in oligotrophic lakes in Kejimkujik National Park, Nova Scotia, Canada. Hydrobiologai 279/280: 57-61.

Kerekes, J., R. Tordon, A. Nieuwburg, and L. Risk. 1994. Fish eating bird abundance in oligotrophic lakes in Kejimkujik National Park, Nova Scotia, Canada. Hydrobiologai 279/280: 57-61. Kerlinger, P. 1982. The migration of common loons through eastern New York. Condor 84:97-100.

Kerlinger, P. 1982. The migration of common loons through eastern New York. Condor 84:97-100. Koel, T.M., L.M. Tronstad, J.L. Arnold, K.A. Gunter, D.W. Smith, J.M. Syslo, and P.J. White. 2019. Predatory fish invasion induces within and across ecosystem effects in Yellowstone National Park. Science Advances 5:eaav1139.

Koel, T.M., L.M. Tronstad, J.L. Arnold, K.A. Gunter, D.W. Smith, J.M. Syslo, and P.J. White. 2019. Predatory fish invasion induces within and across ecosystem effects in Yellowstone National Park. Science Advances 5:eaav1139. Lenard, S., J. Carlson, J. Ellis, C. Jones, and C. Tilly. 2003. P. D. Skaar's Montana bird distribution, 6th edition. Montana Audubon, Helena, MT. 144 pp.

Lenard, S., J. Carlson, J. Ellis, C. Jones, and C. Tilly. 2003. P. D. Skaar's Montana bird distribution, 6th edition. Montana Audubon, Helena, MT. 144 pp. Locke, L.M., S.M. Kerr, and D. Zoromski. 1982. Lead poisoning in common loons (Gavia immer). Avian Diseases 26:392-6.

Locke, L.M., S.M. Kerr, and D. Zoromski. 1982. Lead poisoning in common loons (Gavia immer). Avian Diseases 26:392-6. McEneaney, T. 1988. Status of the common loon in Yellowstone National Park. Pp. 117-129 in: Paul Strong, (ed.), Papers from the 1987 conference on loon research and management. North American Loon Fund, Meredith, NH. 214 pp.

McEneaney, T. 1988. Status of the common loon in Yellowstone National Park. Pp. 117-129 in: Paul Strong, (ed.), Papers from the 1987 conference on loon research and management. North American Loon Fund, Meredith, NH. 214 pp. McIntyre, J. W. 1983. Nurseries: A Consideration of Habitat Requirements During the Early Chick-Rearing Period in Common Loons. Journal of Field Ornithology 54(3):247-253.

McIntyre, J. W. 1983. Nurseries: A Consideration of Habitat Requirements During the Early Chick-Rearing Period in Common Loons. Journal of Field Ornithology 54(3):247-253. McIntyre, J. W., and J. F. Barr. 1983. Pre-migratory behavior of common loons on the autumn staging grounds. Wilson Bulletin 95:121-5.

McIntyre, J. W., and J. F. Barr. 1983. Pre-migratory behavior of common loons on the autumn staging grounds. Wilson Bulletin 95:121-5. McIntyre, J.W. 1994. Loons in freshwater lakes. Hydrobiologia 279/280:393-413.

McIntyre, J.W. 1994. Loons in freshwater lakes. Hydrobiologia 279/280:393-413. Mcintyre, J.W. and J.F. Barr. 1997. Common Loon (Gavia immer). Species Account Number 313. The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology; Retrieved 3/25/2008 from The Birds of North America Online database

Mcintyre, J.W. and J.F. Barr. 1997. Common Loon (Gavia immer). Species Account Number 313. The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology; Retrieved 3/25/2008 from The Birds of North America Online database McPeek, G. A., and D. C. Evers. 1989. Guidelines for the protection and management of the common loon in southwest Michigan: a recovery plan. Kalamazoo Nature Center, Kalamazoo, Michigan. Unpublished report.

McPeek, G. A., and D. C. Evers. 1989. Guidelines for the protection and management of the common loon in southwest Michigan: a recovery plan. Kalamazoo Nature Center, Kalamazoo, Michigan. Unpublished report. Miller, E., and T. Dring. 1988. Territorial defense of multiple lakes by common loons: a preliminary report. Pages 1-14 in P. I. V. Strong (editor). Conf. on Common Loon Res. and Manage., North American Loon Fund, Meredith, New Hampshire.

Miller, E., and T. Dring. 1988. Territorial defense of multiple lakes by common loons: a preliminary report. Pages 1-14 in P. I. V. Strong (editor). Conf. on Common Loon Res. and Manage., North American Loon Fund, Meredith, New Hampshire. Montana Bird Distribution Committee. 1996. P. D. Skaar's Montana Bird Distribution, Fifth Edition. Special Publication No. 3. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena. 130 pp.

Montana Bird Distribution Committee. 1996. P. D. Skaar's Montana Bird Distribution, Fifth Edition. Special Publication No. 3. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena. 130 pp. MT Fish, Wildlife & Parks. No date. Blackfoot-Clearwater Wildlife Management Area checklist.

MT Fish, Wildlife & Parks. No date. Blackfoot-Clearwater Wildlife Management Area checklist. Nelson, J. S. 1983. The tropical fish fauna in Cave and Basin Hotsprings drainage, Banff National Park, Alberta. Canadian Field-Naturalist 97:255-261.

Nelson, J. S. 1983. The tropical fish fauna in Cave and Basin Hotsprings drainage, Banff National Park, Alberta. Canadian Field-Naturalist 97:255-261. Okoniewski, J.C. and W.B. Stone. 1987. Some observations on the morbidity and mortality of, and environmental contaminants in, common loons (Gavia immer) in New York, 1972-1986. New York State Department Environmental Conservation, Delmar, New York. Unpublished Report.

Okoniewski, J.C. and W.B. Stone. 1987. Some observations on the morbidity and mortality of, and environmental contaminants in, common loons (Gavia immer) in New York, 1972-1986. New York State Department Environmental Conservation, Delmar, New York. Unpublished Report. Parker, B. J., P. McKee, and R. R. Campbell. 1988 Status of the redside dace, Clinostomus elongatus, in Canada. Canadian Field-Naturalist 102:163-169.

Parker, B. J., P. McKee, and R. R. Campbell. 1988 Status of the redside dace, Clinostomus elongatus, in Canada. Canadian Field-Naturalist 102:163-169. Parker, K. E., and R. L. Miller. 1988. Status of New York's common loon population--comparison of two intensive surveys. Pages 145-56 in P. I. V. Strong (editor). 1987 Conference on Common Loon Research and Management. North American Loon Fund, Meredith, New Hamphire.

Parker, K. E., and R. L. Miller. 1988. Status of New York's common loon population--comparison of two intensive surveys. Pages 145-56 in P. I. V. Strong (editor). 1987 Conference on Common Loon Research and Management. North American Loon Fund, Meredith, New Hamphire. Paugh, J. I. 2006. Common Loon nesting ecology in northwest Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 90 p.

Paugh, J. I. 2006. Common Loon nesting ecology in northwest Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 90 p. Pokras, M.A., and R. Chafel. 1992. Lead toxicosis from ingested fishing sinkers in adult Common Loons (Gavia immer) in New England. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 23(1):92-97.

Pokras, M.A., and R. Chafel. 1992. Lead toxicosis from ingested fishing sinkers in adult Common Loons (Gavia immer) in New England. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 23(1):92-97. Powers, K. D., and J. Cherry. 1983. Loon migrations off the northeastern United States. Wilson Bulletin 95:125-32.

Powers, K. D., and J. Cherry. 1983. Loon migrations off the northeastern United States. Wilson Bulletin 95:125-32. Ream, C.H. 1976. Loon productivity, human disturbance and pesticide residues in northern Minnesota. Wilson Bulletin 88:427-432.

Ream, C.H. 1976. Loon productivity, human disturbance and pesticide residues in northern Minnesota. Wilson Bulletin 88:427-432. Reidman, M. L., and J. A. Estes. 1988. Predation on seabirds by sea otters. Can. J. Zool. 66:1396-1402.

Reidman, M. L., and J. A. Estes. 1988. Predation on seabirds by sea otters. Can. J. Zool. 66:1396-1402. Reiser, M. H. 1988. Productivity and nest site selection of common loons in a regulated lake system. Pages 15-6 in P. I. V. Strong (editor). 1987 Conference on Common Loon Research and Management. North American Loon Fund, Meredith, New Hampshire

Reiser, M. H. 1988. Productivity and nest site selection of common loons in a regulated lake system. Pages 15-6 in P. I. V. Strong (editor). 1987 Conference on Common Loon Research and Management. North American Loon Fund, Meredith, New Hampshire Rimmer, C. C. 1992. Common loon, Gavia immer. Pages 3-30 in K. J. Schneider and D. M. Pence, editors. Migratory nongame birds of management concern in the Northeast. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Newton Corner, Massachusetts. 400 pp.

Rimmer, C. C. 1992. Common loon, Gavia immer. Pages 3-30 in K. J. Schneider and D. M. Pence, editors. Migratory nongame birds of management concern in the Northeast. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Newton Corner, Massachusetts. 400 pp. Rimmer, C. C., and D. E. Kaveney. 1988. The breeding status of common loons in Vermont--1988. Vermont Inst. Nat. Sci., Woodstock, Vermont. Unpublished report.

Rimmer, C. C., and D. E. Kaveney. 1988. The breeding status of common loons in Vermont--1988. Vermont Inst. Nat. Sci., Woodstock, Vermont. Unpublished report. Root, T. L. 1988. Atlas of wintering North American birds: An analysis of Christmas Bird Count data. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. 312 pp.

Root, T. L. 1988. Atlas of wintering North American birds: An analysis of Christmas Bird Count data. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. 312 pp. Ruggles, A.K. 1994. Habitat selection by loons in southcentral Alaska. Hydrobiologia 279/280: 421-430.

Ruggles, A.K. 1994. Habitat selection by loons in southcentral Alaska. Hydrobiologia 279/280: 421-430. Salt, W.R. and J.R. Salt. 1976. The birds of Alberta. Hurtig Publishers, Edmonton, Alberta. xv + 498 pp.

Salt, W.R. and J.R. Salt. 1976. The birds of Alberta. Hurtig Publishers, Edmonton, Alberta. xv + 498 pp. Saunders, A.A. 1914. The birds of Teton and northern Lewis & Clark counties, Montana. Condor 16:124-144.

Saunders, A.A. 1914. The birds of Teton and northern Lewis & Clark counties, Montana. Condor 16:124-144. Schladweiler, Philip, and John P. Weigand., 1983, Relationships of endrin and other chlorinated hydrocarbon compounds to wildlife in Montana, 1981-1982. September 1983.

Schladweiler, Philip, and John P. Weigand., 1983, Relationships of endrin and other chlorinated hydrocarbon compounds to wildlife in Montana, 1981-1982. September 1983. Sibley, D. 2014. The Sibley guide to birds. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY. 598 pp.

Sibley, D. 2014. The Sibley guide to birds. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY. 598 pp. Skaar, D. 1985. The Montana loon study: 3rd annual report. Unpublished report. 6 pp.

Skaar, D. 1985. The Montana loon study: 3rd annual report. Unpublished report. 6 pp. Skaar, D. 1988. Creation of a management plan for the common loon in Montana. Pages 101-102 in: North American Loon Fund conference report (B88NOR01).

Skaar, D. 1988. Creation of a management plan for the common loon in Montana. Pages 101-102 in: North American Loon Fund conference report (B88NOR01). Skaar, P. D., D. L. Flath, and L. S. Thompson. 1985. Montana bird distribution. Montana Academy of Sciences Monograph 3(44): ii-69.

Skaar, P. D., D. L. Flath, and L. S. Thompson. 1985. Montana bird distribution. Montana Academy of Sciences Monograph 3(44): ii-69. Skaar, P.D. 1969. Birds of the Bozeman latilong: a compilation of data concerning the birds which occur between 45 and 46 N. latitude and 111 and 112 W. longitude, with current lists for Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, impinging Montana counties and Yellowstone National Park. Bozeman, MT. 132 p.

Skaar, P.D. 1969. Birds of the Bozeman latilong: a compilation of data concerning the birds which occur between 45 and 46 N. latitude and 111 and 112 W. longitude, with current lists for Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, impinging Montana counties and Yellowstone National Park. Bozeman, MT. 132 p. Smith, E. L. 1981. Effects of canoeing on common loon production and survival on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge, Alaska. Thesis. Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. 53 p.

Smith, E. L. 1981. Effects of canoeing on common loon production and survival on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge, Alaska. Thesis. Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. 53 p. St. John, P. 1993. Yodelers of the north. American Birds 47(2):202-209.

St. John, P. 1993. Yodelers of the north. American Birds 47(2):202-209. Stewart, R.E. 1975. Breeding birds of North Dakota. Tri-College Center for Environmental Studies, Fargo, North Dakota. 295 pp.

Stewart, R.E. 1975. Breeding birds of North Dakota. Tri-College Center for Environmental Studies, Fargo, North Dakota. 295 pp. Strong, P. I. V. 1985. Habitat selection by common loons. University of Maine, Orono, Maine. Ph.D. dissertation.

Strong, P. I. V. 1985. Habitat selection by common loons. University of Maine, Orono, Maine. Ph.D. dissertation. Strong, P. I. V. 1989. Feeding and chick-rearing areas of common loons. Journal of Wildlife Management 53:72-6.

Strong, P. I. V. 1989. Feeding and chick-rearing areas of common loons. Journal of Wildlife Management 53:72-6. Stroud, R. K., and R. E. Lange. 1983. Information summary: Common loon die-off winter and spring of 1983. Natl. Wildl. Health Lab., U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Madison, Wisconsin.

Stroud, R. K., and R. E. Lange. 1983. Information summary: Common loon die-off winter and spring of 1983. Natl. Wildl. Health Lab., U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Madison, Wisconsin. Sutcliffe, S. A. 1978. Pesticide levels and shell thickness of common loon eggs in New Hampshire. Wilson Bulletin 90:637-40.

Sutcliffe, S. A. 1978. Pesticide levels and shell thickness of common loon eggs in New Hampshire. Wilson Bulletin 90:637-40. Swan River National Wildlife Refuge. 1982. Birds of the Swan River NWR. Kalispell, MT: NW MT Fish and Wildlife Center pamphlet.

Swan River National Wildlife Refuge. 1982. Birds of the Swan River NWR. Kalispell, MT: NW MT Fish and Wildlife Center pamphlet. Thompson, L.S. 1981. Circle West wildlife monitoring study: Third annual report. Technical report No. 8. Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation. Helena, Montana.

Thompson, L.S. 1981. Circle West wildlife monitoring study: Third annual report. Technical report No. 8. Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation. Helena, Montana. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). 1987. Migratory Nongame Birds of Management Concern in the United States: The 1987 List. Office of Migratory Bird Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. 63 pp.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). 1987. Migratory Nongame Birds of Management Concern in the United States: The 1987 List. Office of Migratory Bird Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. 63 pp. U.S. Forest Service. 1991. Forest and rangeland birds of the United States: Natural history and habitat use. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Agricultural Handbook 688. 625 pages.

U.S. Forest Service. 1991. Forest and rangeland birds of the United States: Natural history and habitat use. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Agricultural Handbook 688. 625 pages. Vermeer, K. 1973. Some aspects of the breeding and mortality of common loons in east-central Alberta. Canadian Field-Naturalist 87:403-8.

Vermeer, K. 1973. Some aspects of the breeding and mortality of common loons in east-central Alberta. Canadian Field-Naturalist 87:403-8. Vermeer, K. 1973. Some aspects of the nesting requirements of Common Loons in Alberta. Wilson Bulletin 85:429-435.

Vermeer, K. 1973. Some aspects of the nesting requirements of Common Loons in Alberta. Wilson Bulletin 85:429-435. Watts, C.R. and L.C. Eichhorn. 1981. Changes in the birds of central Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 40:31-40.

Watts, C.R. and L.C. Eichhorn. 1981. Changes in the birds of central Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 40:31-40. Williams, L. E. 1973. Spring migration of common loons from the Gulf of Mexico. Wilson Bulletin 85:238.

Williams, L. E. 1973. Spring migration of common loons from the Gulf of Mexico. Wilson Bulletin 85:238. Wood, R. L. 1979. Management of breeding loon populations in New Hampshire. Pages 141-6 in S. Sutcliffe (editor). Proceedings of the Second North American Conference on Common Loon Research and Management. National Audubon Society, New York, New York.

Wood, R. L. 1979. Management of breeding loon populations in New Hampshire. Pages 141-6 in S. Sutcliffe (editor). Proceedings of the Second North American Conference on Common Loon Research and Management. National Audubon Society, New York, New York. Zicus, M. C., R. H. Hier, and S. J. Maxson. 1983. A common loon nest from Minnesota containing four eggs. Wilson Bulletin 95:672-3.

Zicus, M. C., R. H. Hier, and S. J. Maxson. 1983. A common loon nest from Minnesota containing four eggs. Wilson Bulletin 95:672-3. Zimmer, G. E. 1979. The status and distribution of the common loon in Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point, Wisconsin. M.S. thesis.

Zimmer, G. E. 1979. The status and distribution of the common loon in Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point, Wisconsin. M.S. thesis.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Common Loon"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Birds"